| variable | description |

|---|---|

| S | Subject Number |

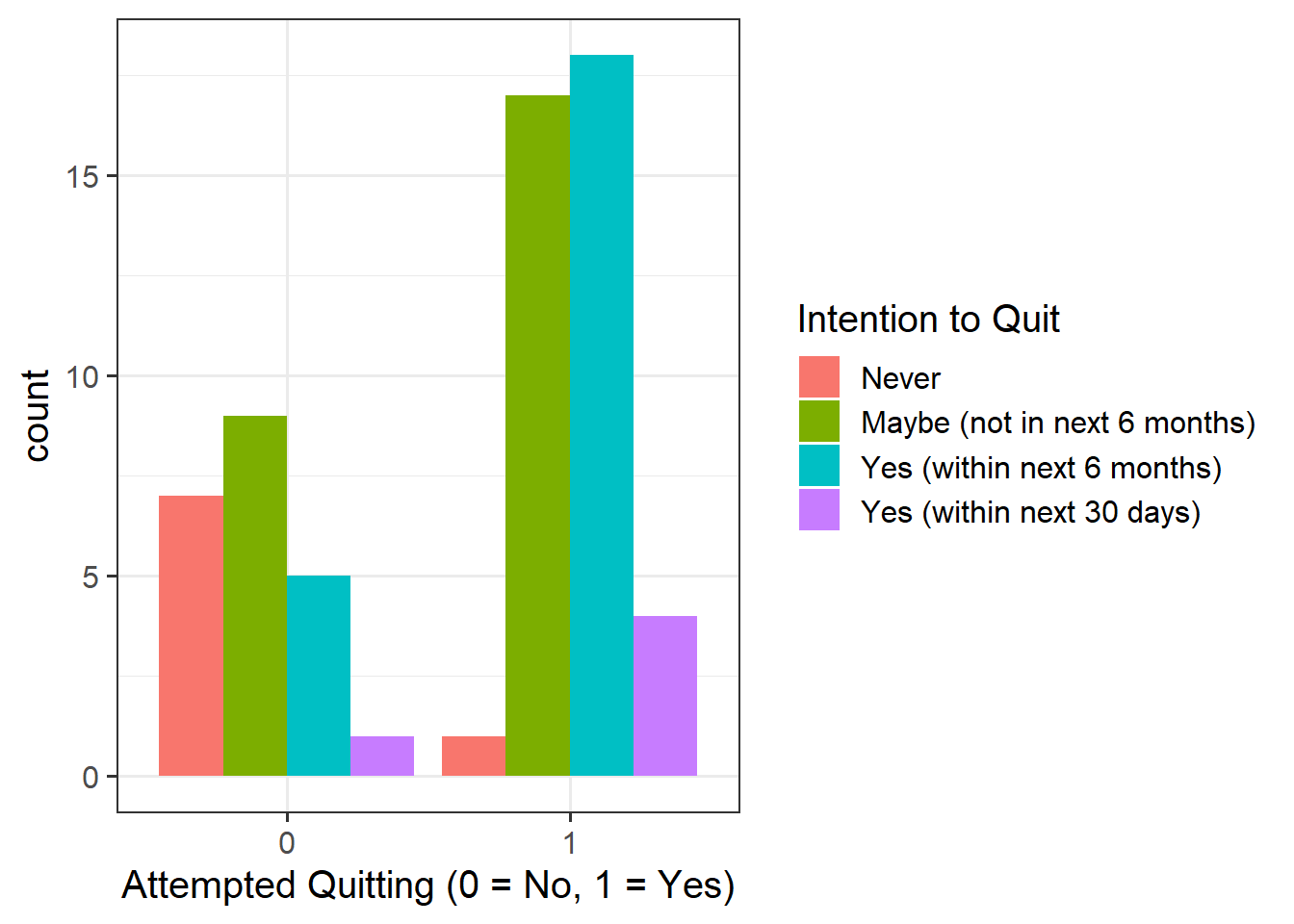

| Q | Quit attempt - Whether the subject made an attempt to quit using tobacco products (0 = no attempt to quit; 1 = attempted to quit). |

| I | Individuals intention to quit (1 = Never intend to quit; 2 = May intend to quit but not in the next 6 months; 3 = Intend to quit in the next 6 months; 4 = Intend to quit in the next 30 days) |

Logistic Regression II

Learning Objectives

At the end of this lab, you will:

- Understand when to use a logistic model

- Understand how to fit and interpret a logistic model

- Understand how to evaluate model fit

What You Need

- Be up to date with lectures

- Have completed previous lab exercises from Semester 2 Week 7

Required R Packages

Remember to load all packages within a code chunk at the start of your RMarkdown file using library(). If you do not have a package and need to install, do so within the console using install.packages(" "). For further guidance on installing/updating packages, see Section C here.

For this lab, you will need to load the following package(s):

- tidyverse

- patchwork

- kableExtra

- psych

- sjPlot

Presenting Results

All results should be presented following APA guidelines.If you need a reminder on how to hide code, format tables/plots, etc., make sure to review the rmd bootcamp.

The example write-up sections included as part of the solutions are not perfect - they instead should give you a good example of what information you should include and how to structure this. Note that you must not copy any of the write-ups included below for future reports - if you do, you will be committing plagiarism, and this type of academic misconduct is taken very seriously by the University. You can find out more here.

Lab Data

You can download the data required for this lab here or read it in via this link https://uoepsy.github.io/data/QuitAttempts.csv

Study Overview

Research Question

Is attempting to quit tobacco products associated with an individuals intentions?

Setup

- Create a new RMarkdown file

- Load the required package(s)

- Read in the QuitAttempts dataset into R, assigning it to an object named

smoke

Exercises

Study & Analysis Plan Overview

Examine the dataset, and perform any necessary and appropriate data management steps.

- The

str()function will return the overall structure of the dataset, this can be quite handy to look at

- Convert categorical variables to factors, and if needed, provide better variable names

- Label factors appropriately to aid with your model interpretations if required

- Check that the dataset is complete (i.e., are there any

NAvalues?). We can check this usingis.na()

Note that all of these steps can be done in combination - the mutate() and factor() functions will likely be useful here.

Descriptive Statistics & Visualisations

Provide a table of descriptive statistics and visualise your data.

Remember to interpret these in the context of the study.

Review the many ways to numerically and visually explore your data by reading over the data exploration flashcards.

For examples, see flashcards on descriptives statistics tables - categorical and numeric values examples.

Specifics to consider:

For your table of descriptive statistics, both the

group_by()andsummarise()functions will come in handy hereFor your visualisations, you will need to specify

as_factor()when plotting the quit attempt variable since this is numeric, but we want it to be treated as a factor only for plotting purposes

Model Fitting & Interpretation

Fit your model using glm(), and assign it as an object with the name “smoke_mdl1”.

For an overview of how to fit a binary logistic regression model using the glm() function, see the binary logistic regression flashcard.

For an example, review the binary logistic regression - example flashcard.

Interpret your coefficients in the context of the study. When doing so, it may be useful to translate the log-odds back into odds.

For an overview of how probability, odds, and log-odds are related, review the probability, odds, and log-odds flashcard.

If you need help interpreting coefficients, review the interpretation of coefficients flashcard.

For an example, review the binary logistic regression - example flashcard.

Calculate the predicted probability of each group attempting to quit smoking.

For an overview of how probability, odds, and log-odds are related, review the probability, odds, and log-odds flashcard.

To calculate via R, as you will see from the flashcard, you can use the predict, or plogis() functions.

For the former, you will need to specify type = "response" to obtain the predicted probabilities, and this requires the model coefficients to be in log-odds. When specifying newdata =, it might be useful to ask for each unique level of our “Intention” variable. This is very similar in procedure to how you’ve done this in the past. For a recap, see the model predicted values and residuals flashcard. For the latter, we can calculate the probability corresponding to a given value of logit(p).

Model Fit

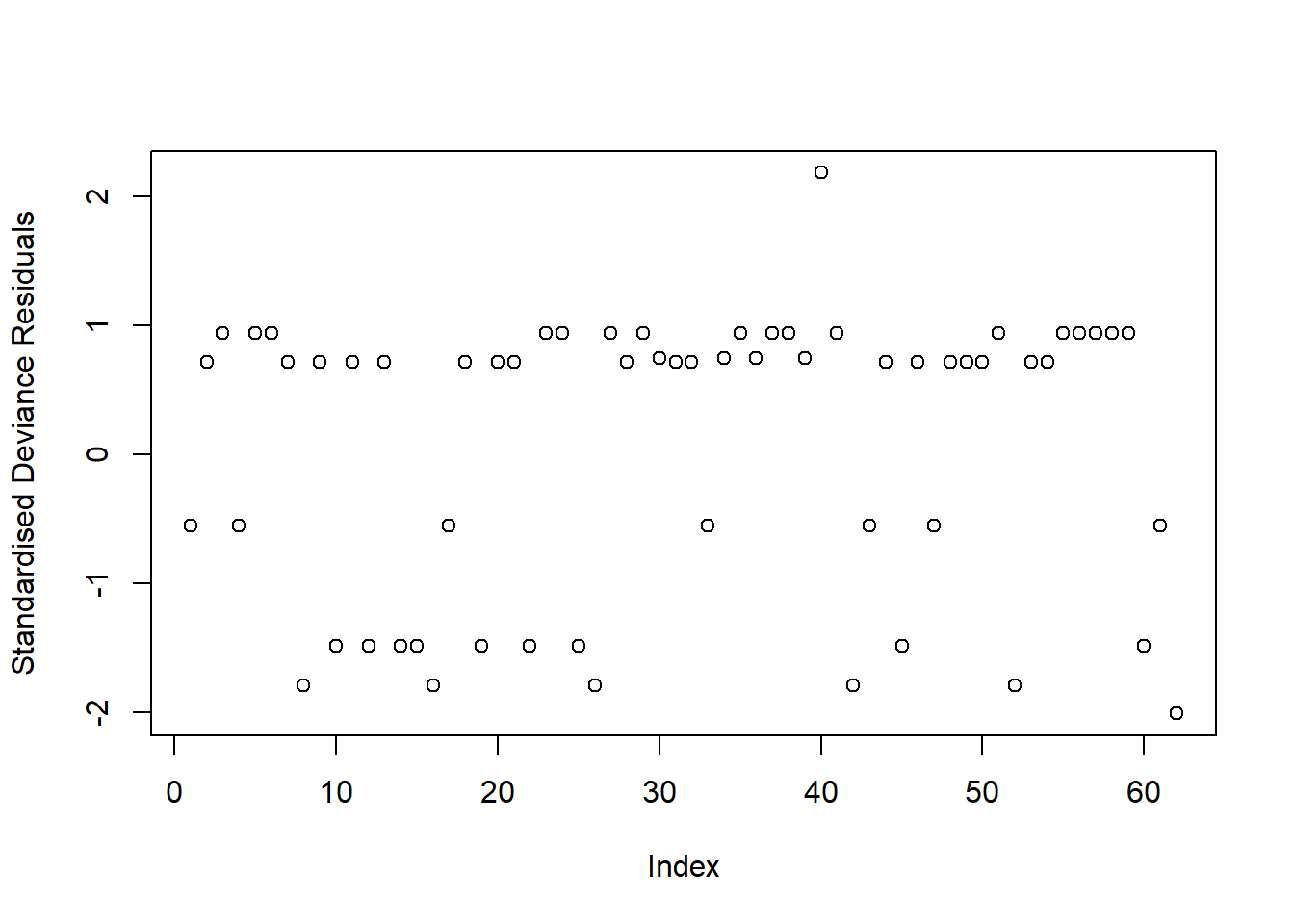

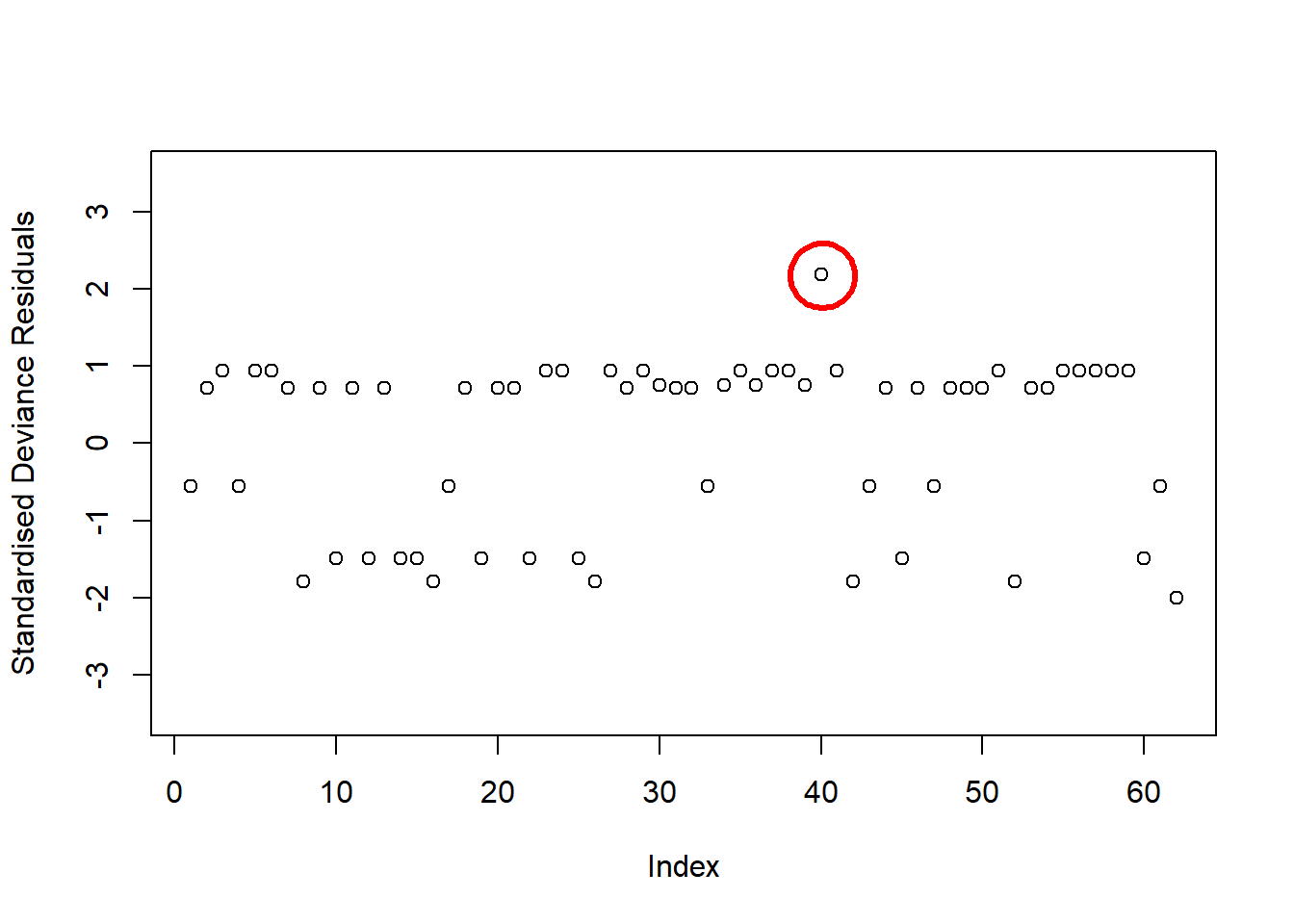

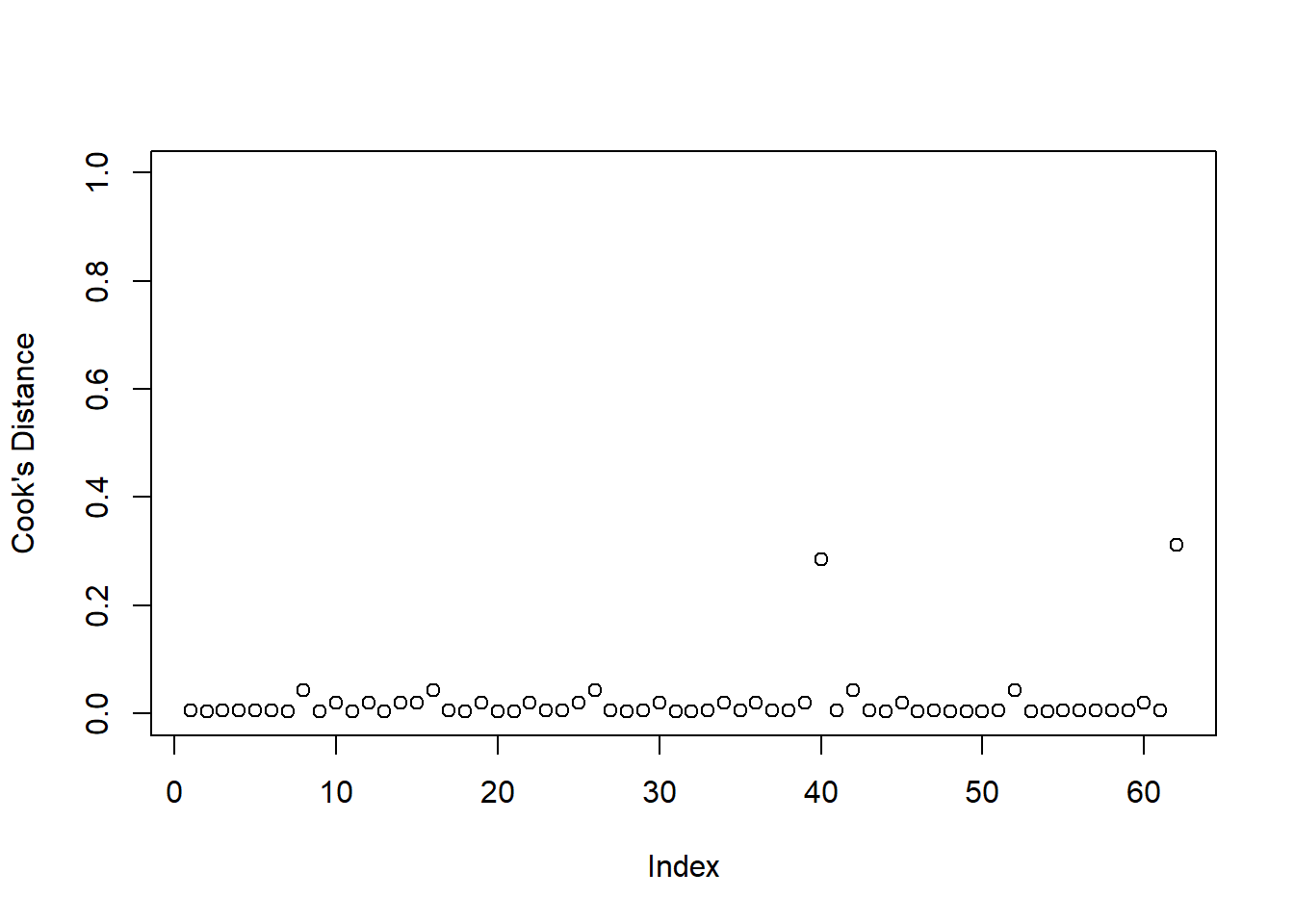

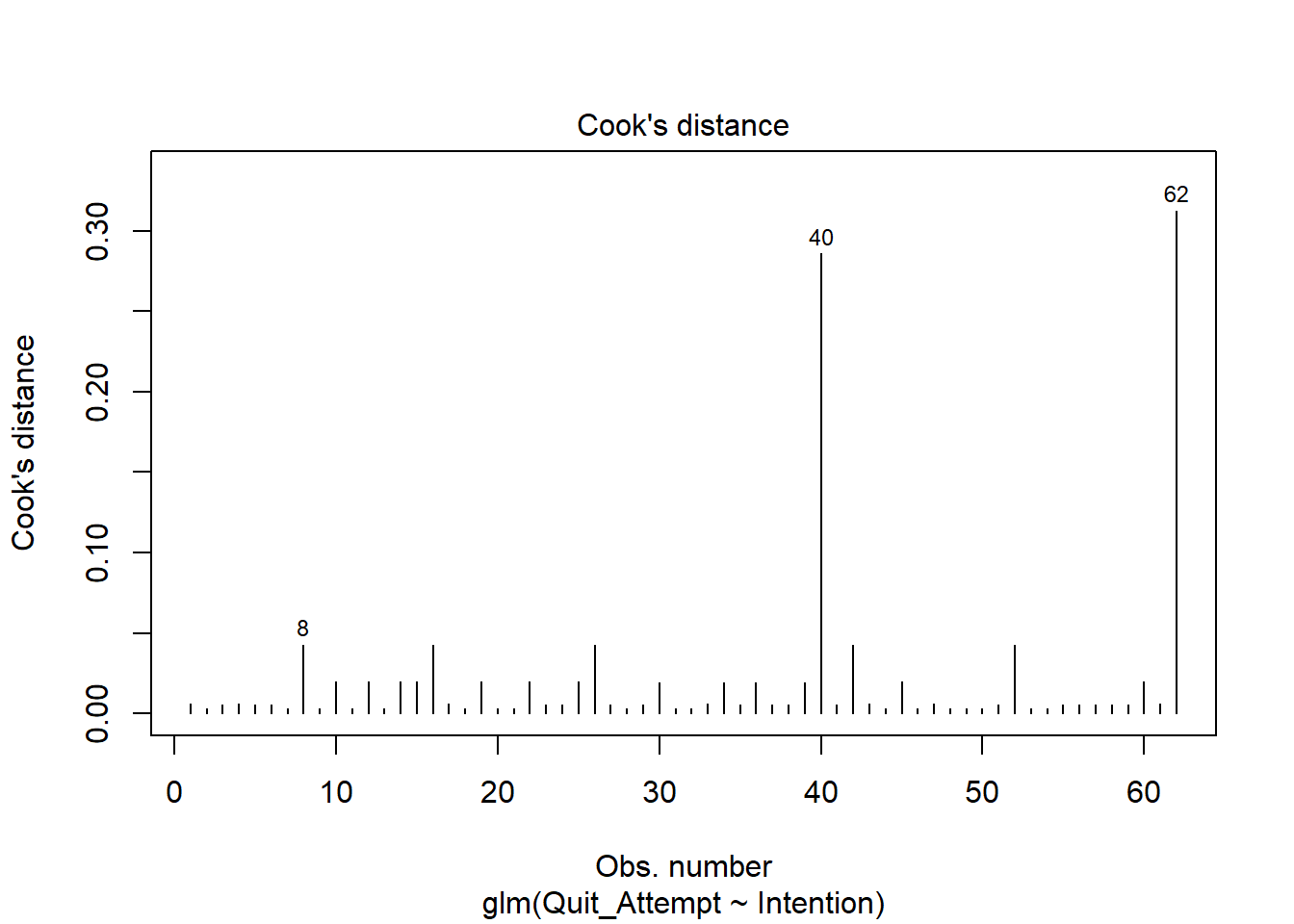

Examine the below plot to determine if the deviance residuals raise concerns about outliers:

Based on this plot, are there any residuals of concern? Are there any additional plots you could check to determine if there are influential observations?

For an overview of logistic model assumptions, review the deviance residuals and high influence cases flashcards.

Perform a Deviance goodness-of-fit test to compare your fitted model to the null (denoted as \(M_1\) and \(M_0\) respectively below).

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{M}_0 &: \qquad \log \left( \frac{p}{1 - p}\right) ~=~ \beta_0 \\ \text{M}_1 &: \qquad \log \left( \frac{p}{1 - p}\right) ~=~ \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \text{Intention}_\text{2} + \beta_2 \cdot \text{Intention}_\text{3} + \beta_3 \cdot \text{Intention}_\text{4} \end{aligned} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{where}~{p}~ &=~ \text{probability of attempting to quit using tobacco products} \end{aligned} \]

Report the results of the model comparison in APA format, and state which model you think best fits the data.

Consider whether or not your models are nested. The model comparisons - logistic regression flashcards may be helpful to revisit.

Check the AIC and BIC values for smoke_mdl0 and smoke_mdl1 - which model should we prefer based on these model fit indices?

Writing Up & Presenting Results

Provide key model results in a formatted table.

Use tab_model() from the sjPlot package. For a quick guide, review the tables flashcard.

Interpret your results in the context of the research question and report your model in full.

Make reference to the regression table.

For an example of coefficient interpretation, review the interpretation of coefficients flashcard.

Compile Report

Knit your report to PDF, and check over your work. To do so, you should make sure:

- Only the output you want your reader to see is visible (e.g., do you want to hide your code?)

- Check that the tinytex package is installed

- Ensure that the ‘yaml’ (bit at the very top of your document) looks something like this:

---

title: "this is my report title"

author: "B1234506"

date: "07/09/2024"

output: bookdown::pdf_document2

---If you are having issues knitting directly to PDF, try the following:

- Knit to HTML file

- Open your HTML in a web-browser (e.g. Chrome, Firefox)

- Print to PDF (Ctrl+P, then choose to save to PDF)

- Open file to check formatting

To not show the code of an R code chunk, and only show the output, write:

```{r, echo=FALSE}

# code goes here

```To show the code of an R code chunk, but hide the output, write:

```{r, results='hide'}

# code goes here

```To hide both code and output of an R code chunk, write:

```{r, include=FALSE}

# code goes here

```You must make sure you have tinytex installed in R so that you can “Knit” your Rmd document to a PDF file:

install.packages("tinytex")

tinytex::install_tinytex()

Footnotes

Kalkhoran, S., Grana, R. A., Neilands, T. B., & Ling, P. M. (2015). Dual use of smokeless tobacco or e-cigarettes with cigarettes and cessation. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39(2), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.2.14↩︎