| Item | Statement |

|---|---|

| Item_1 | I often felt an inability to concentrate |

| Item_2 | I frequently forgot things |

| Item_3 | I found thinking clearly required a lot of effort |

| Item_4 | I often felt happy |

| Item_5 | I had lots of energy |

| Item_6 | I worked efficiently |

| Item_7 | I often felt irritable |

| Item_8 | I often felt stressed |

| Item_9 | I often felt sleepy |

| Item_10 | I often felt fatigued |

Week 5 Exercises: Cov, Cor, Models

Q1: Go to http://guessthecorrelation.com/ and play the “guess the correlation” game for a little while to get an idea of what different strengths and directions of \(r\) can look like.

Sleepy time

Data: Sleep levels and daytime functioning

A researcher is interested in the relationship between hours slept per night and self-rated effects of sleep on daytime functioning. She recruited 50 healthy adults, and collected data on the Total Sleep Time (TST) over the course of a seven day period via sleep-tracking devices.

At the end of the seven day period, participants completed a Daytime Functioning (DTF) questionnaire. This involved participants rating their agreement with ten statements (see Table 1). Agreement was measured on a scale from 1-5. An overall score of daytime functioning can be calculated by:

- reversing the scores for items 4,5 and 6 (because those items reflect agreement with positive statements, whereas the other ones are agreement with negative statement);

- summing the scores on each item; and

- subtracting the sum score from 50 (the max possible score). This will make higher scores reflect better perceived daytime functioning.

The data is available at https://uoepsy.github.io/data/sleepdtf.csv.

Read in the data, and calculate the overall daytime functioning score, following the criteria outlined above. Make this a new column in your dataset.

To reverse items 4, 5 and 6, we we need to make all the scores of 1 become 5, scores of 2 become 4, and so on… What number satisfies all of these equations: ? - 5 = 1, ? - 4 = 2, ? - 3 = 3?

To quickly sum accross rows, you might find the rowSums() function useful (you don’t have to use it though)

Calculate the correlation between the total sleep time (TST) and the overall daytime functioning score calculated in the previous question.

Conduct a test to establish the probability of observing a correlation this strong in a sample of this size assuming the true correlation to be 0.

Write a sentence or two summarising the results.

Hints: You can do this all with one function, see 5A #correlation-test.

Think about this relationship in terms of causation.

Claim: Less sleep causes poorer daytime functioning.

Why might it be inappropriate to make the claim above based on these data alone? Think about what sort of study could provide stronger evidence for such a claim.

Things to think about:

- comparison groups.

- random allocation.

- measures of daytime functioning.

- measures of sleep time.

- other (unmeasured) explanatory variables.

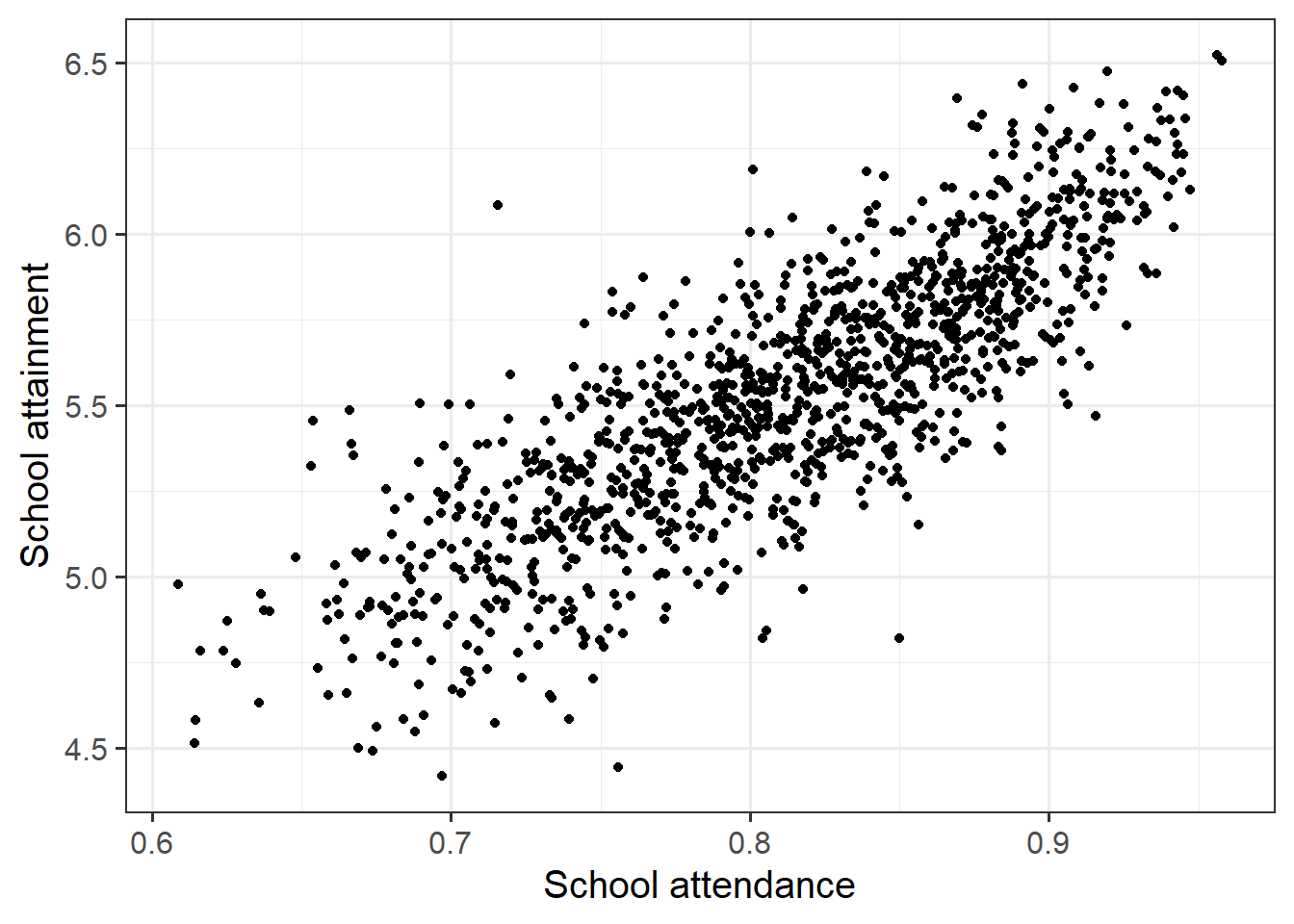

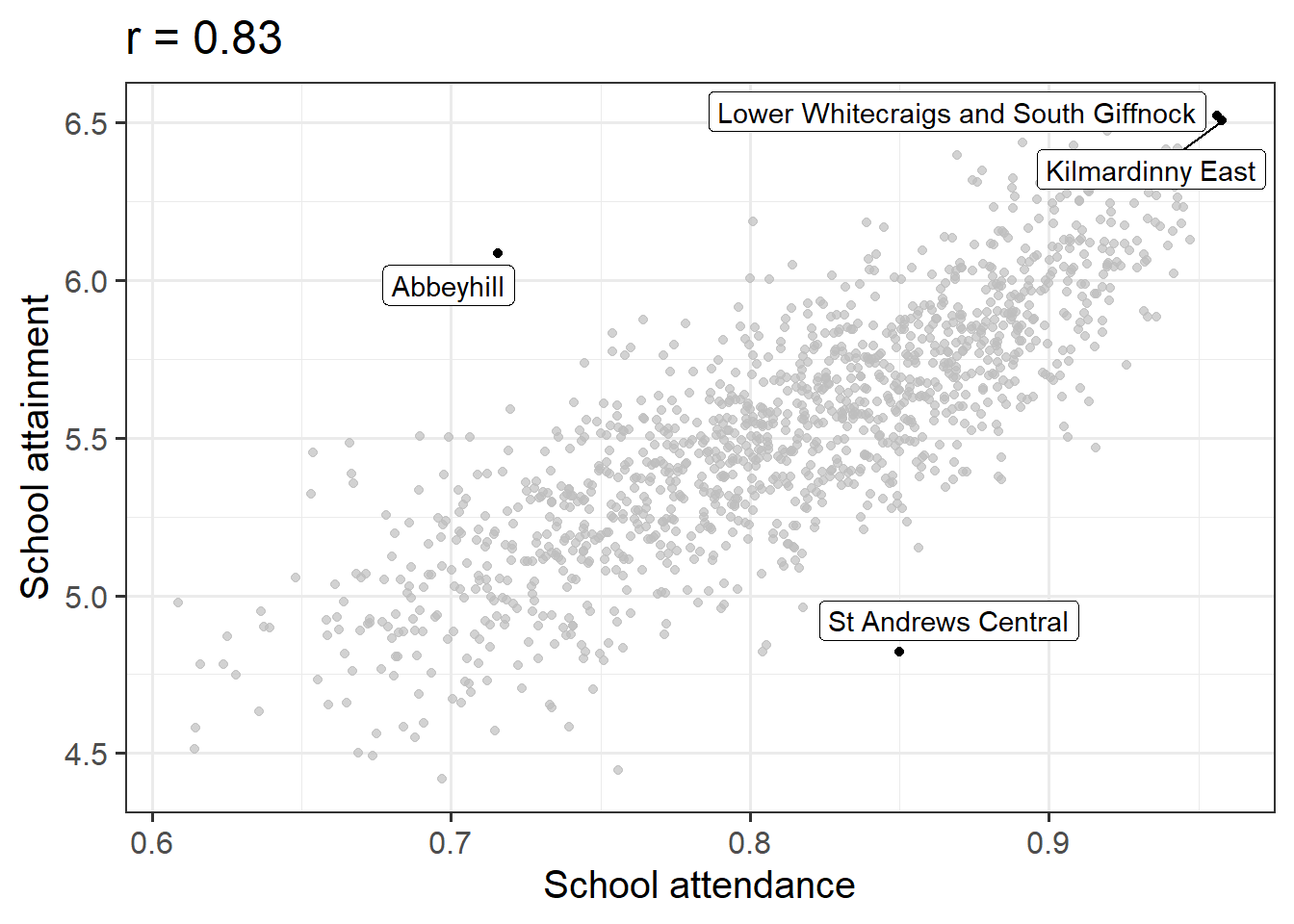

Attendance and Attainment

Data: Education SIMD Indicators

The Scottish Government regularly collates data across a wide range of societal, geographic, and health indicators for every “datazone” (small area) in Scotland.

The dataset at https://uoepsy.github.io/data/simd20_educ.csv contains some of the education indicators (see Table 2).

| variable | description |

|---|---|

| intermediate_zone | Areas of scotland containing populations of between 2.5k-6k household residents |

| attendance | Average School pupil attendance |

| attainment | Average attainment score of School leavers (based on Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF)) |

| university | Proportion of 17-21 year olds entering university |

Conduct a test of whether there is a correlation between school attendance and school attainment in Scotland.

Present and write up the results.

Hints:

The readings have not included an example write-up for you to follow. Try to follow the logic of those for t-tests and \(\chi^2\)-tests.

- describe the relevant data

- explain what test was conducted and why

- present the relevant statistic, degrees of freedom (if applicable), statement on p-value, etc.

- state the conclusion.

Be careful figuring out how many observations your test is conducted on. cor.test() includes only the complete observations.

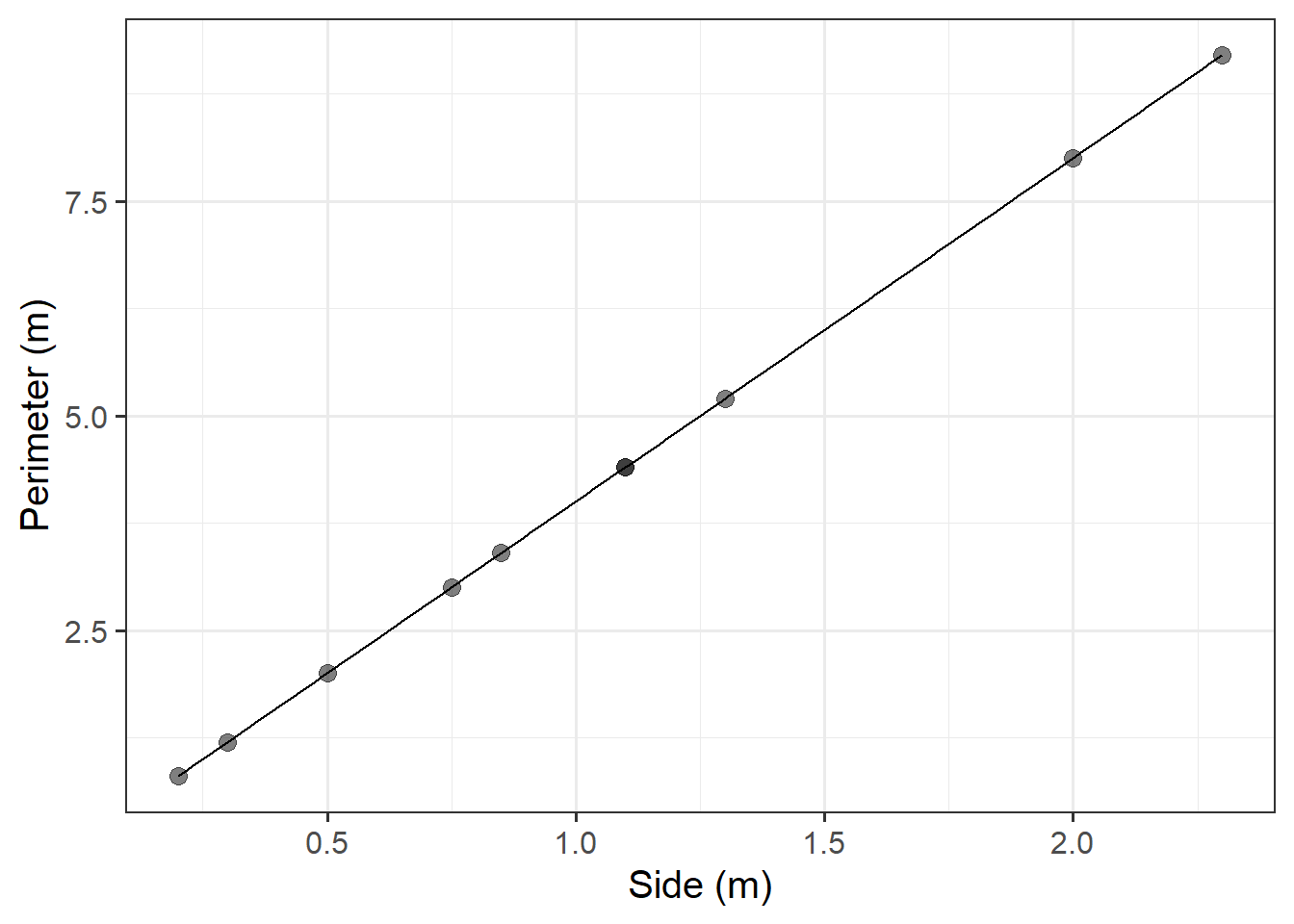

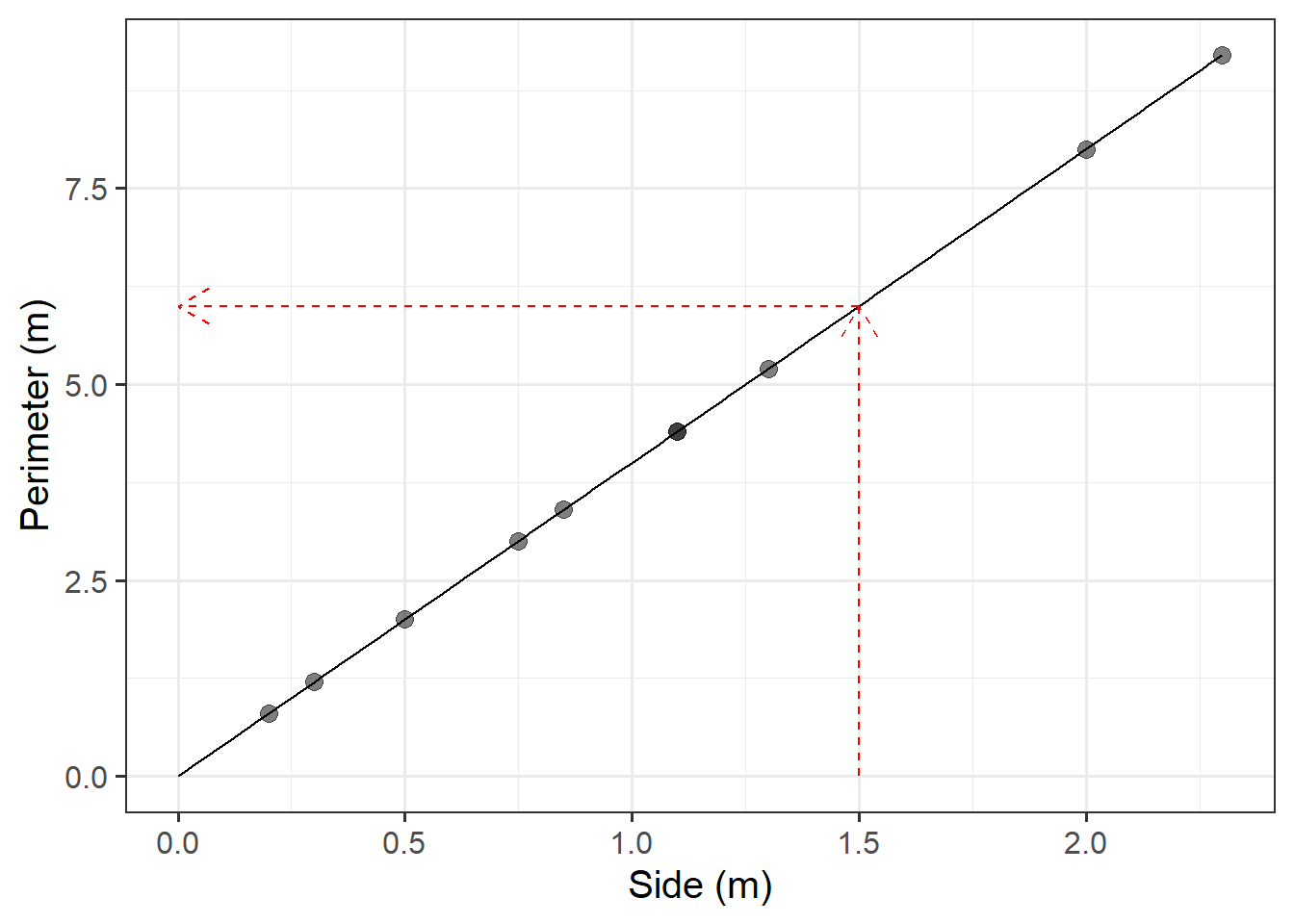

Functions and Models

The Scottish National Gallery kindly provided us with measurements of side and perimeter (in metres) for a sample of 10 square paintings.

The data are provided below:

Note: this is a way of creating a “tibble” (a dataframe in ‘tidyverse-style’ language) in R, rather than reading one in from an external file.

sng <- tibble(

side = c(1.3, 0.75, 2, 0.5, 0.3, 1.1, 2.3, 0.85, 1.1, 0.2),

perimeter = c(5.2, 3.0, 8.0, 2.0, 1.2, 4.4, 9.2, 3.4, 4.4, 0.8)

)Plot the data from the Scottish National Gallery using ggplot(), with the side measurements of the paintings on the x-axis, and the perimeter measurements on the y-axis.

We know that there is a mathematical model for the relationship between the side-length and perimeter of squares: \(perimeter = 4 \times \ side\).

Try adding the following line to your plot:

stat_function(fun = ~.x * 4)

Use our mathematical model to predict the perimeter of a painting with a side of 1.5 metres.

Hints:

We don’t have a painting with a side of 1.5 metres within the random sample of paintings from the Scottish National Gallery, but we can work out the perimeter of an hypothetical square painting with 1.5m sides, using our model - either using the plot from the previous question, or calculating it algebraically.

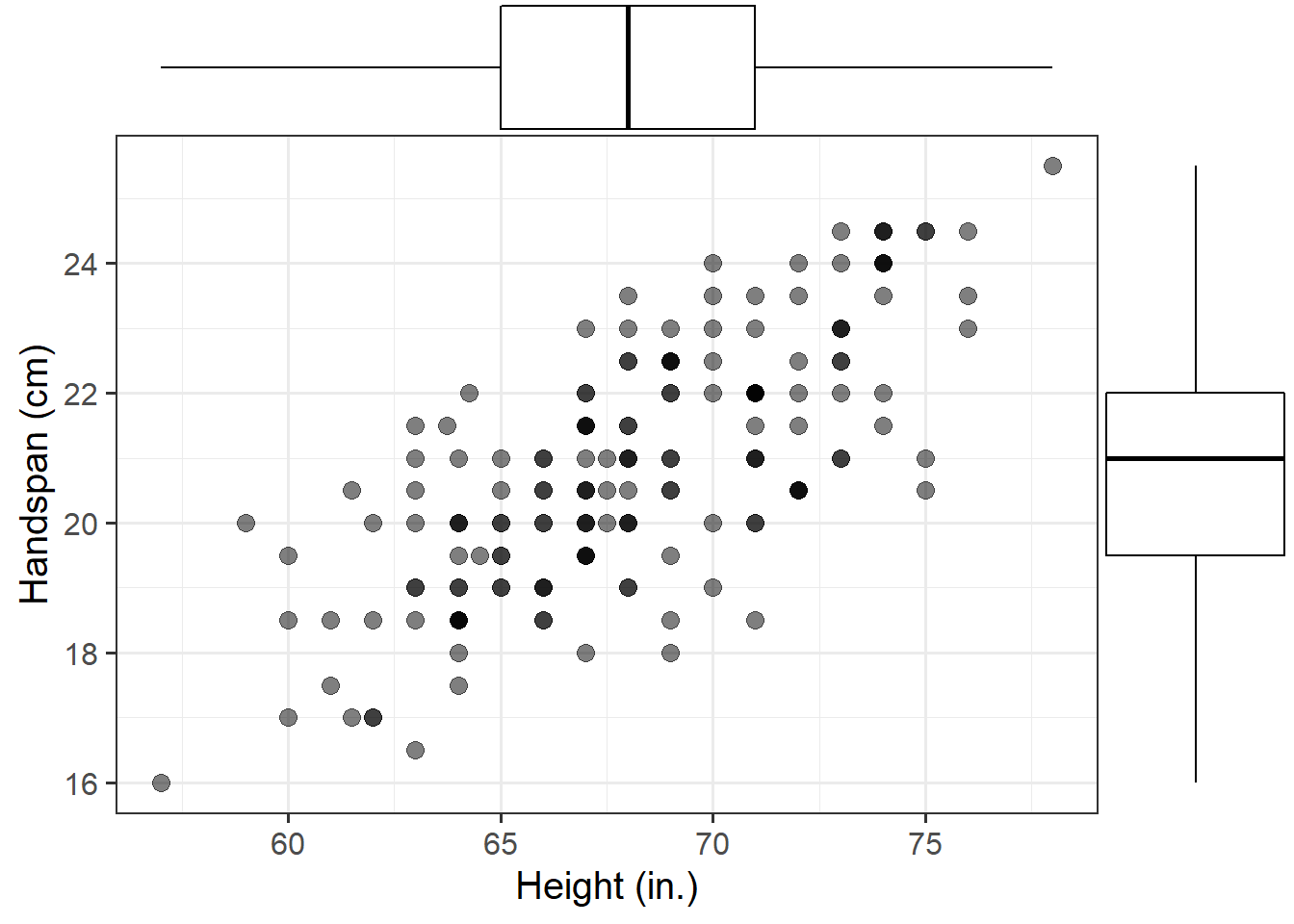

Data: HandHeight

This dataset, from Jessican M Utts and Robert F Heckard. 2015. Mind on Statistics (Cengage Learning)., records the height and handspan reported by a random sample of 167 students as part of a class survey.

The variables are:

height, measured in incheshandspan, measured in centimetres

The data are available at https://uoepsy.github.io/data/handheight.csv

Consider the relationship between height (in inches) and handspan (in cm).

Read the handheight data into R, and investigate (visually) how handspan varies as a function of height for the students in the sample.

Do you notice any outliers or points that do not fit with the pattern in the rest of the data?

Comment on any main differences you notice between this relationship and the relationship between sides and perimeter of squares.

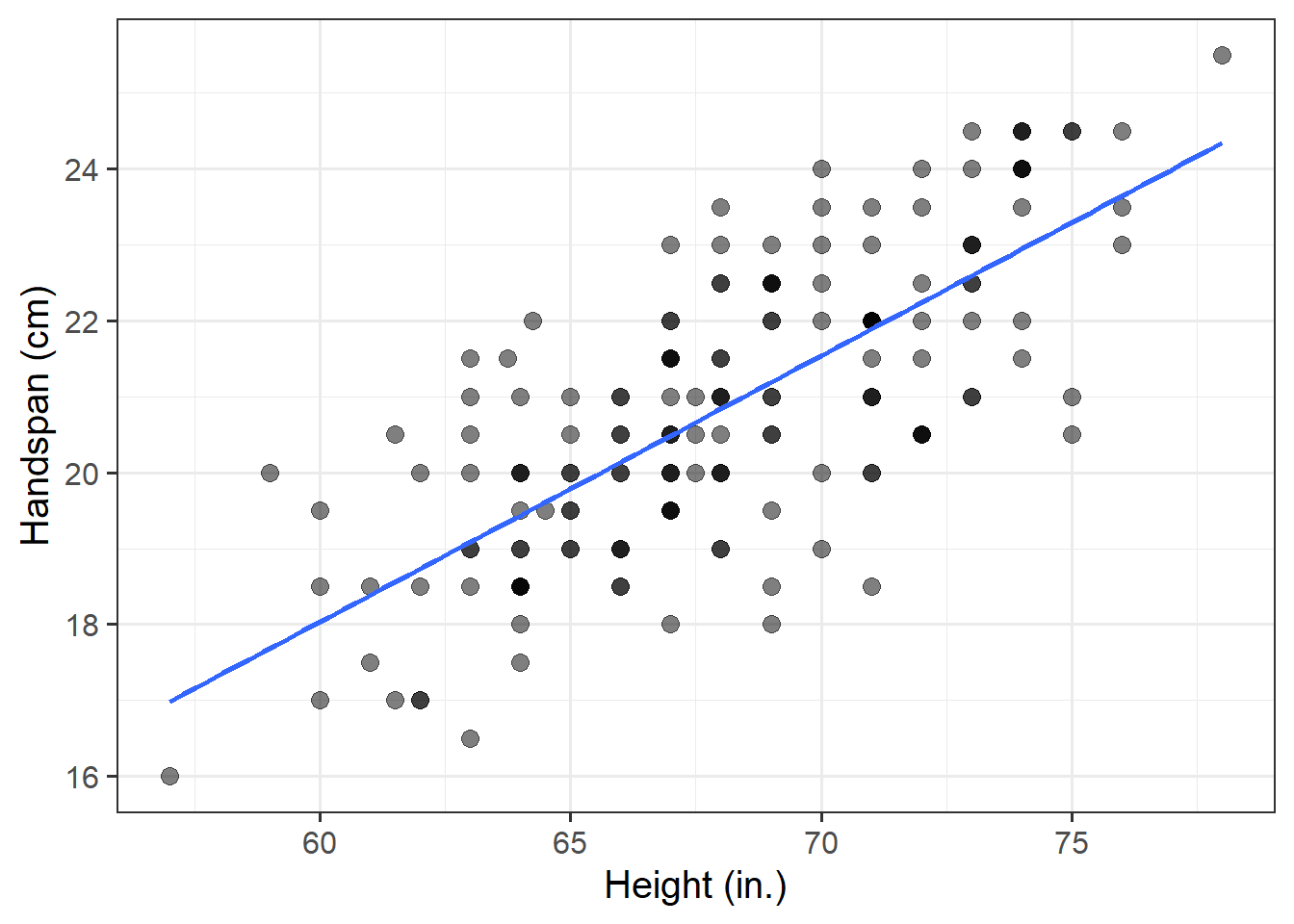

Hopefully, as part of the previous question, you created a scatterplot of handspans against heights. If not, make one now.

Try adding the following line of code to the scatterplot. It will add a best-fit line describing how handspan varies as a function of height. For the moment, the argument se = FALSE tells R to not display uncertainty bands.

geom_smooth(method = lm, se = FALSE)Think about the differences you notice with between this and the figure you made in Question 6.

Relationships such as that between height and handspan show deviations from an “average pattern”. To model this, we need need to create a model that allows for deviations from the linear relationship. This is called a statistical model.

A statistical model includes both a deterministic function and a random error term: \[ Handspan = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \ Height + \epsilon \] or, in short, \[ y = \underbrace{\beta_0 + \beta_1 \ x}_{f(x)} + \underbrace{\epsilon}_{\text{random error}} \]

The deterministic function \(f(x)\) need not be linear if the scatterplot displays signs of nonlinearity, but in this course we focus primarily on linear relationships.

In the equation above, the terms \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) are numbers specifying where the line going through the data meets the y-axis and its slope (rate of increase/decrease).

The line of best-fit is given by:1 \[ \widehat{Handspan} = -3 + 0.35 \ Height \]

What is your best guess for the handspan of a student who is 73in tall?

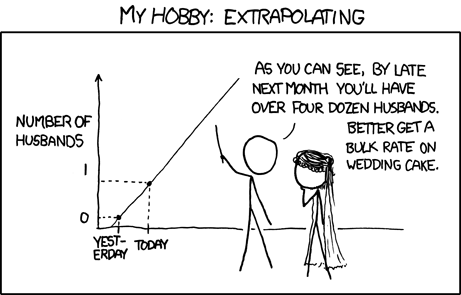

And for students who are 5in?

Footnotes

Yes, the error term is gone. This is because the line of best-fit gives you the prediction of the average handspan for a given height, and not the individual handspan of a person, which will almost surely be different from the prediction of the line.↩︎