load(url("https://uoepsy.github.io/data/Az.rda"))Week 3 Exercises: Non-Linear Change

Cognitive Task Performance

Dataset: Az.rda

These data are available at https://uoepsy.github.io/data/Az.rda. You can load the dataset using:

and you will find the Az object in your environment.

The Az object contains information on 30 Participants with probable Alzheimer’s Disease, who completed 3 tasks over 10 time points: A memory task, and two scales investigating ability to undertake complex activities of daily living (cADL) and simple activities of daily living (sADL). Performance on all of tasks was calculated as a percentage of total possible score, thereby ranging from 0 to 100.

We’re interested in whether performance on these tasks differed at the outset of the study, and if they differed in their subsequent change in performance.

| variable | description |

|---|---|

| Subject | Unique Subject Identifier |

| Time | Time point of the study (1 to 10) |

| Task | Task type (Memory, cADL, sADL) |

| Performance | Score on test (range 0 to 100) |

Load in the data and examine it.

How many participants, how many observations per participant, per task?

No modelling just yet.

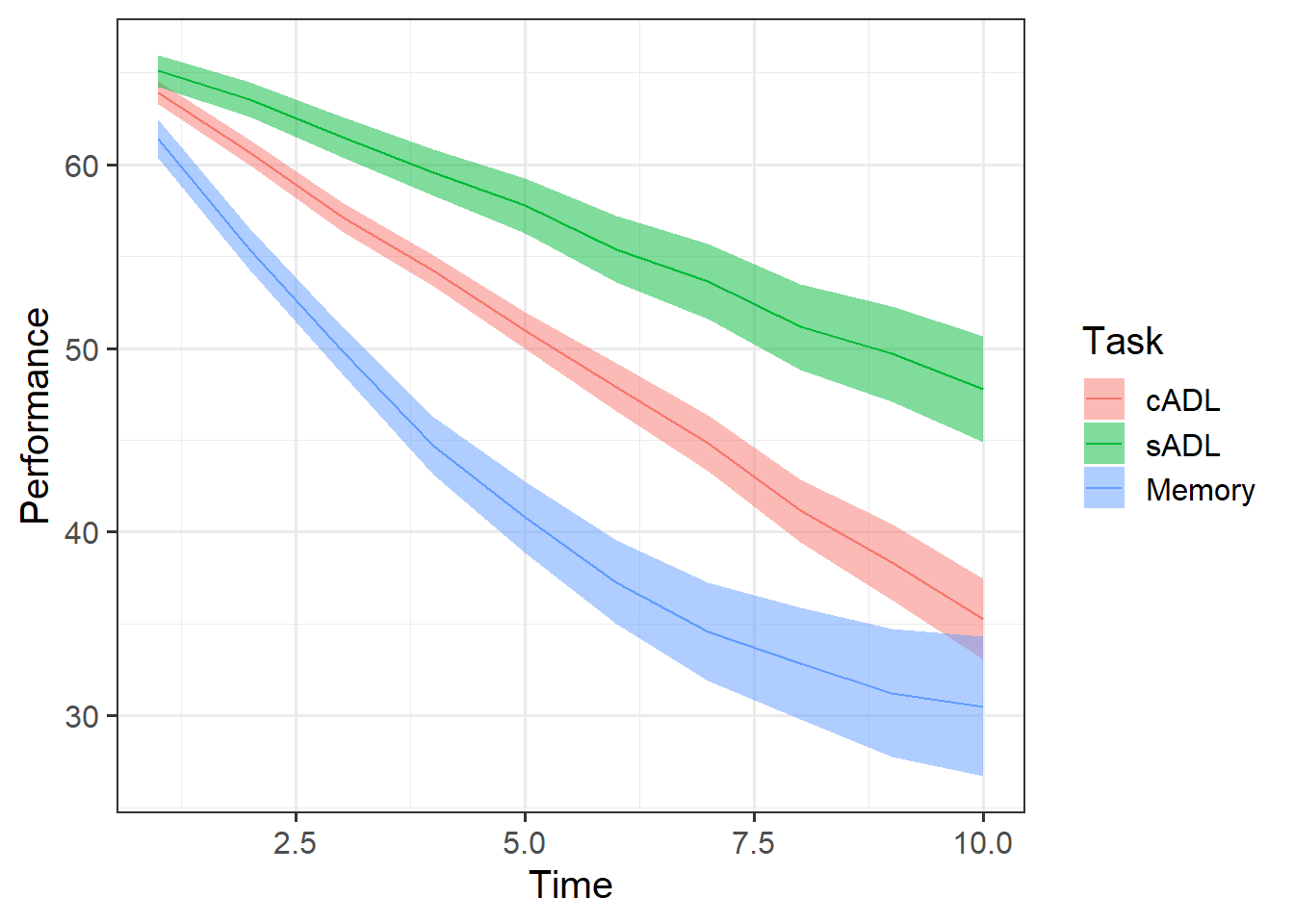

Plot the performance over time for each type of task.

Try using stat_summary so that you are plotting the means (and standard errors) of each task, rather than every single data point. Why? Because this way you can get a shape of the average trajectories of performance over time in each task.

For an example plot, see Chapter 6: polynomial growth #example-in-mlm.

Why do you think raw/natural polynomials might be more useful than orthogonal polynomials for these data?

Are we somewhat interested in group differences (i.e. differences in scores, or differences in rate of change) at a specific point in time?

Re-center the Time variable so that the intercept is the first timepoint.

Then choose an appropriate degree of polynomial (if any), and fit a full model that allows us to address the research aims.

Note there is no part of the research question that specifically asks about how “gradual” or “quick” the change is (which would suggest we are interested in the quadratic term).

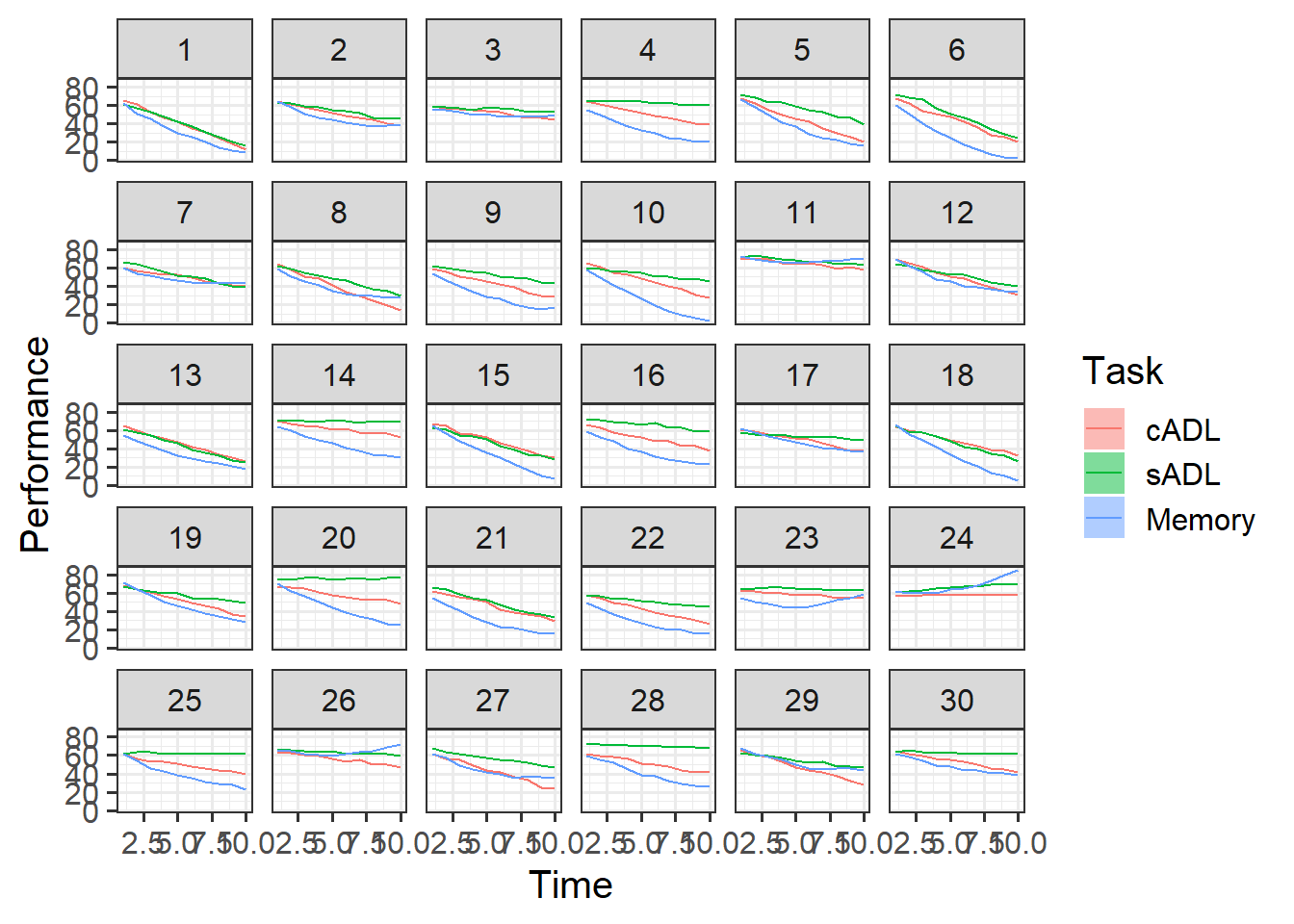

However, plots (summarised at the task level, and of individual participant’s data separately) can help to give us a sense of what degree of polynomial terms might be suitable to succinctly describe the trends.

In many cases, fitting higher and higher order polynomials will likely result in a ‘better fit’ to our sample data, but these will be worse and worse at generalising to new data - i.e. we run the risk of overfitting.

Okay, so the model didn’t converge. It’s trying to estimate a lot of things in the random effects (even though it didn’t converge, try looking at VarCorr(model) to see all the covariances it is trying to estimate).

When we have a categorical random effect (i.e. where the x in (1 + x | g) is a categorical variable), then model estimation can often get tricky, because “the effect of x” for a categorical variable with \(k\) levels is identified via \(k-1\) parameters, meaning we have a lot of variances and covariances to estimate when we include x|g.

When x is numeric:

Groups Name Std.Dev. Corr

g (Intercept) ...

x ... ...

Residual ... When x is categorical with \(k\) levels:

Groups Name Std.Dev. Corr

g (Intercept) ...

xlevel2 ... ...

xlevel3 ... ... ...

... ... ... ... ...

xlevelk ... ... ... ... ...

Residual ... However, we can use an alternative formation of the random effects by putting a categorical x into the right-hand side:

Instead of (1 + x | g) we can fit (1 | g) + (1 | g:x).

The symbol : in g:x is used to refer to the combination of g and x.

g x g:x

1 p1 a p1.a

2 p1 a p1.a

3 p1 b p1.b

4 ... ... ...

5 p2 a p2.a

6 p2 b p2.b

7 ... ... ...It’s a bit weird to think about it, but these two formulations of the random effects can kind of represent the same idea:

(1 + x | g): each group ofgcan have a different intercept and a different effect ofx

(1 | g) + (1 | g:x): each group ofgcan have a different intercept, and each level of x within eachgcan have a different intercept.

Both of these allow the outcome y to change across x differently for each group in g (i.e. both of them result in y being different for each level of x in each group g).

The first does so explicitly by estimating the group level variance of the y~x effect.

The second one estimates the variance of \(y\) between groups, and also the variance of \(y\) between ‘levels of x within groups’. In doing so, it achieves more or less the same thing, but by capturing these as intercept variances between levels of x, we don’t have to worry about lots of covariances:

(1 + x | g)

Groups Name Std.Dev. Corr

g (Intercept) ...

xlevel2 ... ...

xlevel3 ... ... ...

... ... ... ... ...

xlevelk ... ... ... ... ...

Residual ... (1 | g) + (1 | g:x)

Groups Name Std.Dev.

g (Intercept) ...

g.x (Intercept) ...

Residual ... Try adjusting your model by first moving Task to the right hand side of the random effects, and from there starting to simplify things (remove random slopes one-by-one)

This is our first experience of our random effect structures becoming more complex than simply (.... | group). This is going to feel confusing, but don’t worry, we’ll see more structures like this next week.

... + (1 + poly1 + poly2 | Subject) + (1 + poly1 + poly2 | Subject:Task)

To then start simplifying (if this model doesn’t converge), it can be helpful to look at the VarCorr() of the non-converging model to see if anything looks awry. Look for small variances, perfect (or near perfect) correlations. These might be sensible things to remove.

Conduct a series of model comparisons investigating whether

- Tasks differ only in their linear change

- Tasks differ in their quadratic change

Remember, these sorts of model comparisons are being used to isolate and test part of the fixed effects (we’re interested in the how the average participant performs over the study). So our models want to have the same random effect structure, but different fixed effects.

See the end of Chapter 6: polynomial growth #example-in-mlm.

Get some confidence intervals and provide an interpretation of each coefficient from the full model.

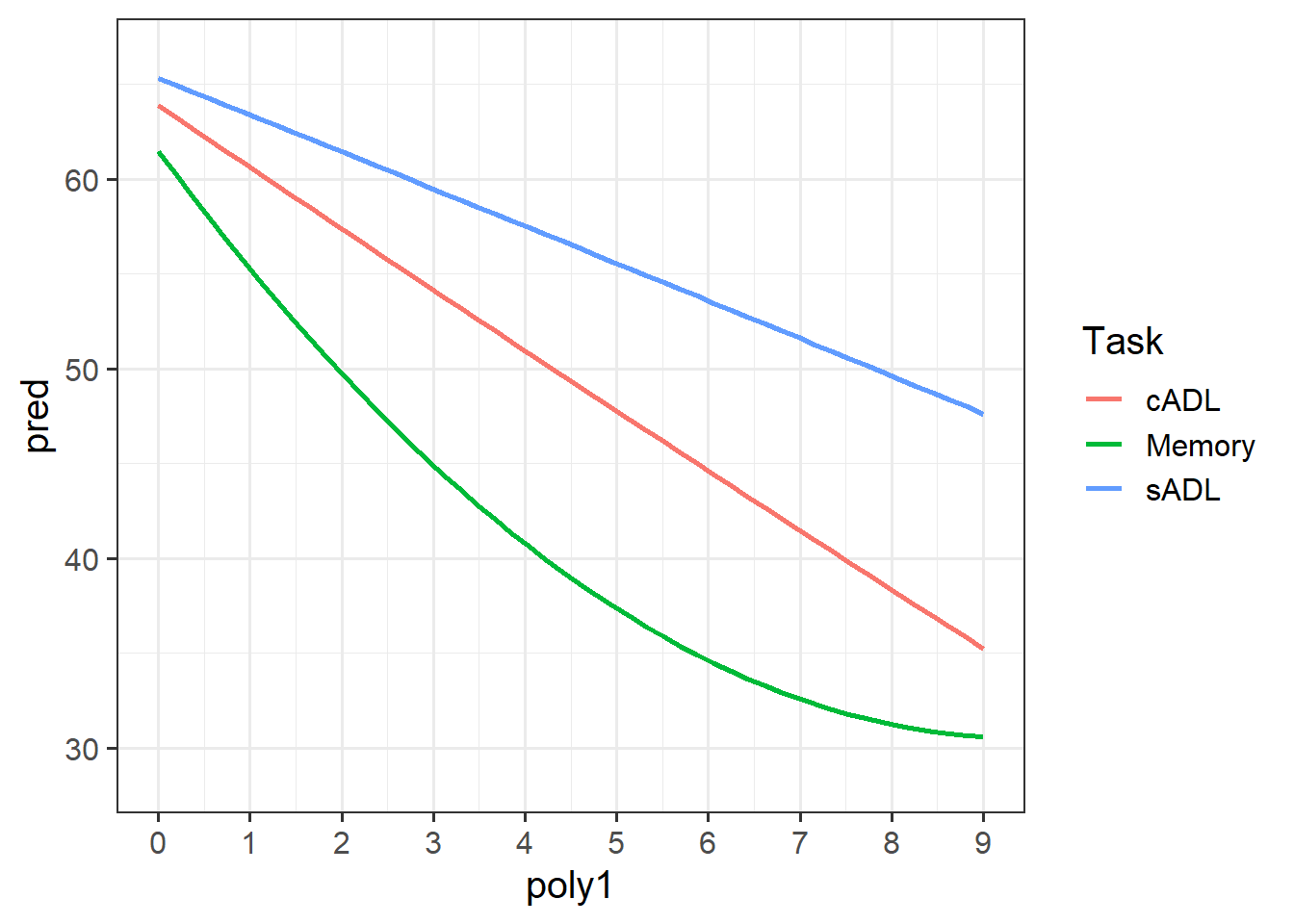

Take a piece of paper, and based on your interpretation for the previous question, sketch out the model estimated trajectories for each task.

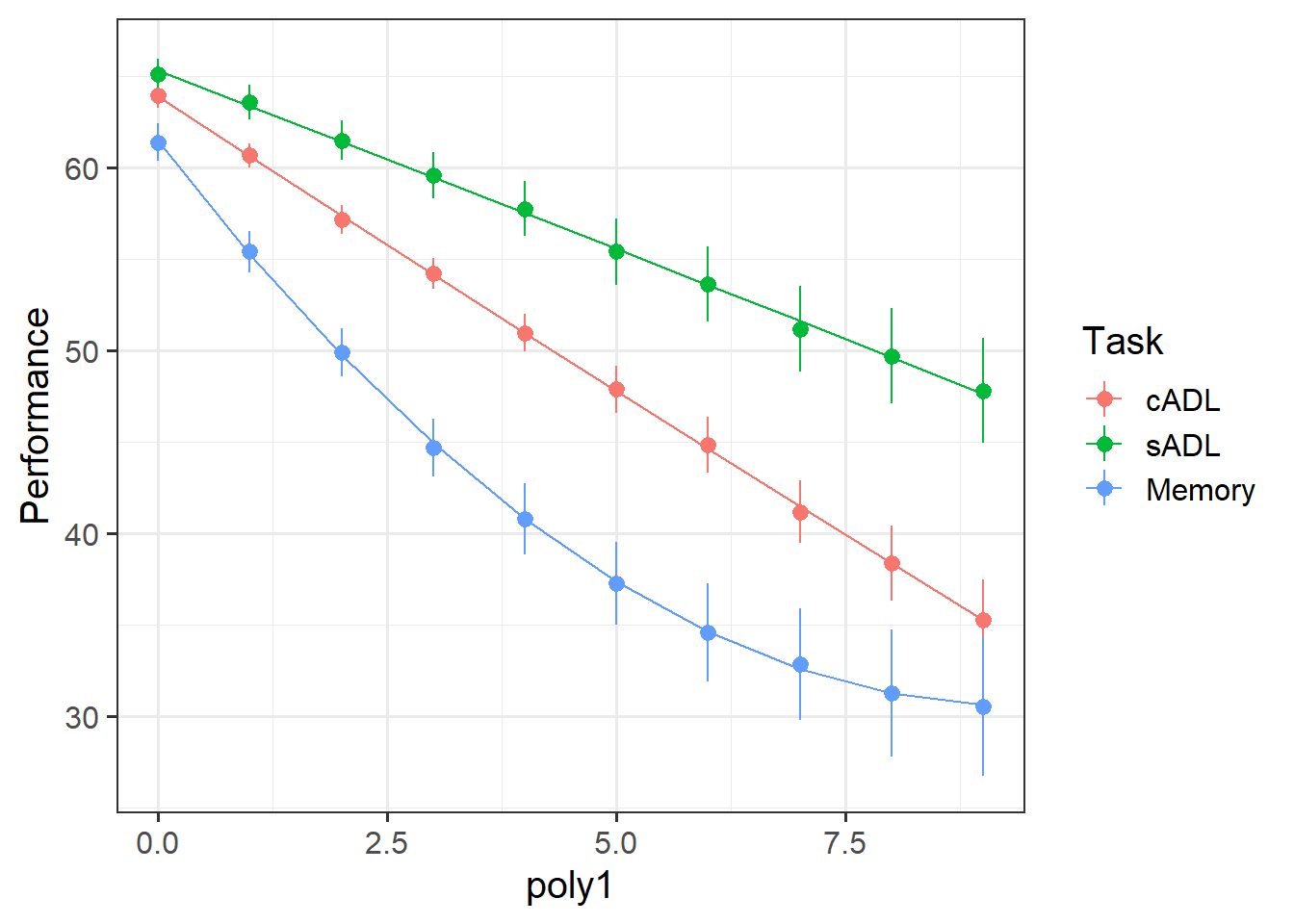

Make a plot showing both the average performance and the average model predicted performance across time.