Categorical predictors and dummy coding

Data Analysis for Psychology in R 2

Department of Psychology

University of Edinburgh

2025–2026

Course Overview

| Introduction to Linear Models | Intro to Linear Regression |

| Interpreting Linear Models | |

| Testing Individual Predictors | |

| Model Testing & Comparison | |

| Linear Model Analysis | |

| Analysing Experimental Studies | Categorical Predictors & Dummy Coding |

| Effects Coding & Coding Specific Contrasts | |

| Assumptions & Diagnostics | |

| Bootstrapping | |

| Categorical Predictor Analysis |

| Interactions | Interactions I |

| Interactions II | |

| Interactions III | |

| Analysing Experiments | |

| Interaction Analysis | |

| Advanced Topics | Power Analysis |

| Binary Logistic Regression I | |

| Binary Logistic Regression II | |

| Logistic Regression Analysis | |

| Exam Prep and Course Q&A |

Warm-up activity: Line drawing

Warm-up activity: Line drawing

Draw each of the lines that’s defined by the given intercept and slope.

Line 1:

- Intercept is 0

- Slope is 1

Line 2:

- Intercept is 1

- Slope is –1

Line 3:

- Intercept is –1

- Slope is 2

This week’s learning objectives

How can we include categorical variables as predictors in a linear model?

When we use a categorical predictor, how do we interpret the linear model’s coefficients?

What hypotheses are tested by the default way that R represents categorical predictors?

If we wanted to test different hypotheses after fitting the model, how would we do that?

Categorical predictors with two levels

Categorical predictors with two levels

aka binary predictors

Categorical predictors with two levels

aka binary predictors

Categorical predictors with two levels

aka binary predictors

But: linear models can only deal with input in number form.

So we need a way to represent the levels of these variables as numbers.

The way we’ll learn about today: dummy coding, aka treatment coding.

Dummy/treatment coding represents one level as 0, and the other level as 1

Schematic:

Studying

aloneis coded as 0.Studying with

othersis coded as 1.

Does it matter which level is coded as 0 and which level is coded as 1?

Yes.

Why does it matter which level is coded as 0

and which level is coded as 1?

To illustrate: Here are test scores from students who studied either alone (blue) or with others (pink).

Why does it matter which level is coded as 0

and which level is coded as 1?

A linear model will fit a line to this data.

Before I show you this line, I want you to make predictions about it.

Predict individually: Write down your guesses:

- The line’s intercept will be the same as the mean of either alone or others. Which one? Why?

- Will the slope of the line be positive or negative? Why?

Explain in pairs/threes: Why do you think your guesses are likely to be correct?

How to choose appropriate reference level?

Each level of your categorical predictor will be compared against the reference level (aka the baseline).

Useful reference levels might be:

- The control group in a study

- The group expected to have the lowest score on the outcome

- The largest group

The reference level should not be:

- A poorly-defined level, e.g., category

Other(because interpreting the coefficients will be weird/tricky) - Much smaller than the other groups (because estimates based on smaller amounts of data tend to be less trustworthy)

Testing differences between levels

Testing differences between levels

We can find parameters values all on our own, without a linear model.

But we need a linear model to answer research questions like:

Do students who study with others score significantly better than students who study alone?

To answer this question, we’ll fit a model that predicts score as a function of study patterns: score ~ study.

Modelling score ~ study

Call:

lm(formula = score ~ study, data = score_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-22.79 -4.79 0.21 5.48 18.21

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 22.79 0.66 34.51 < 2e-16 ***

studyothers 4.73 1.01 4.69 0.0000045 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 7.9 on 248 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.0815, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0777

F-statistic: 22 on 1 and 248 DF, p-value: 0.00000453Model evaluation works the same as before

\(R^2\):

- Still tells us how much variance in the data is accounted for by the model.

Multiple R-squared: 0.0815, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0777 \(F\)-ratio (aka \(F\)-statistic):

- Still tells us the ratio of explained variance to unexplained variance.

- Still tests the hypothesis that all regression slopes in the model = 0.

F-statistic: 22 on 1 and 248 DF, p-value: 0.00000453(Revisit Lecture 4 for a refresher!)

What hypotheses are being tested for each coefficient?

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 22.79 0.66 34.51 1.12e-96

studyothers 4.73 1.01 4.69 4.53e-06(Intercept) aka \(\beta_0\):

- Null hypothesis (aka H0): the intercept is equal to zero (aka \(\beta_0 = 0\)).

- \(p\)-value (aka

Pr(>|t|)): the probability of observing an intercept of 22.79, assuming that the true value of the intercept is zero.

studyothers aka \(\beta_1\):

- Null hypothesis (aka H0): the difference between levels is equal to zero (aka \(\beta_1 = 0\)).

- \(p\)-value: the probability of observing a difference of 4.73, assuming that the true value of the difference is zero.

Our research question was about how studying alone or with others is associated with test score.

Are both of these hypothesis tests relevant to our research question?

Reporting the model’s estimates

Study habits significantly predicted student test scores, F(1, 248) = 21.992, p < 0.001.

Study habits explained 8.15% of the variance in test scores.

Specifically, students who studied with others (M = 27.52, SD = 7.94) scored significantly higher than students who studied alone (M = 22.79, SD = 7.86), \(\beta_1\) = 4.73, SE = 1.01, t = 4.69, p < 0.001.

Specifically, students who studied with others (M = `r round(mean_others, 2)`, SD = `r round(sd_others, 2)`) scored significantly higher than students who studied alone (M = `r round(mean_alone, 2)`, SD = `r round(sd_alone, 2)`), $\beta_1$ = `r round( summary(m1)$coefficients['studyothers', 'Estimate'], 2)`, SE = `r round( summary(m1)$coefficients['studyothers', 'Std. Error'], 2)`, t = `r summary(m1)$coefficients['studyothers', 't value']`, p < 0.001.We always have time for your questions

It’s OK if your questions are only half-baked right now and you don’t know exactly what to ask. There’s a lot of information here!

Here are some good starting points:

“I’m not certain about [keyword]. Can you go over that again?”

“What does [keyword] have to do with [keyword]?”

“Why would we even want to do [keyword]?”

If you ask your questions, it’s a good thing for all of us!

Visualising the model’s predictions

Visualising the model’s predictions

We have almost all the pieces!

But finding the SE for the non-reference level is mathematically a little complicated.

A nice shortcut: an R package called emmeans.

emmeans = “Estimated Marginal Means”

- “Estimated” \(\rightarrow\) based on a model’s estimates

- “Marginal” \(\rightarrow\) for each level of a predictor, with the other predictors held constant

- “Means” \(\rightarrow\) averages (and confidence intervals!) of the estimated outcomes for each level of the predictor

emmeans = “Estimated Marginal Means”

Use emmeans() to get each group’s estimated mean and the variability associated with it.

study emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL

alone 22.8 0.660 248 21.5 24.1

others 27.5 0.763 248 26.0 29.0

Confidence level used: 0.95 lower.CL and upper.CL are our 95% confidence intervals.

Plotting marginal means and CIs

emmeans has a built-in plot style.

It’s OK, but a bit boring. We can definitely do better.

Plotting marginal means and CIs

# Save EMMs in tibble format,

# with compatible column names

m1_emm_df <- m1_emm |>

as_tibble() |>

rename(score = emmean)

# Plot the data like before,

# and now overlay EMMs

score_data |>

ggplot(aes(x = study, y = score, fill = study, colour = study)) +

geom_violin(alpha = 0.5) +

geom_jitter(alpha = 0.5, width = 0.3, size = 5) +

theme(legend.position = 'none') +

scale_colour_manual(values = pal) +

scale_fill_manual(values = pal) +

geom_errorbar(

data = m1_emm_df,

aes(ymin = lower.CL, ymax = upper.CL),

colour = 'black',

width = 0.2,

linewidth = 2

) +

geom_point(

data = m1_emm_df,

colour = 'black',

size = 5

)emmeans is an amazingly useful tool.

It can do LOTS more than we’ve seen here!

We’ll see more examples in the coming days and weeks.

Building an analysis workflow

Extension: Changing the reference level

If reference level = alone:

If reference level = others:

When others is the reference level (that is, the level represented as 0):

- What does the intercept represent?

- What does the slope represent?

- Why is the slope negative now, when before it was positive?

- Challenge: What hypotheses would a linear model test about this data?

Categorical predictors with >2 levels

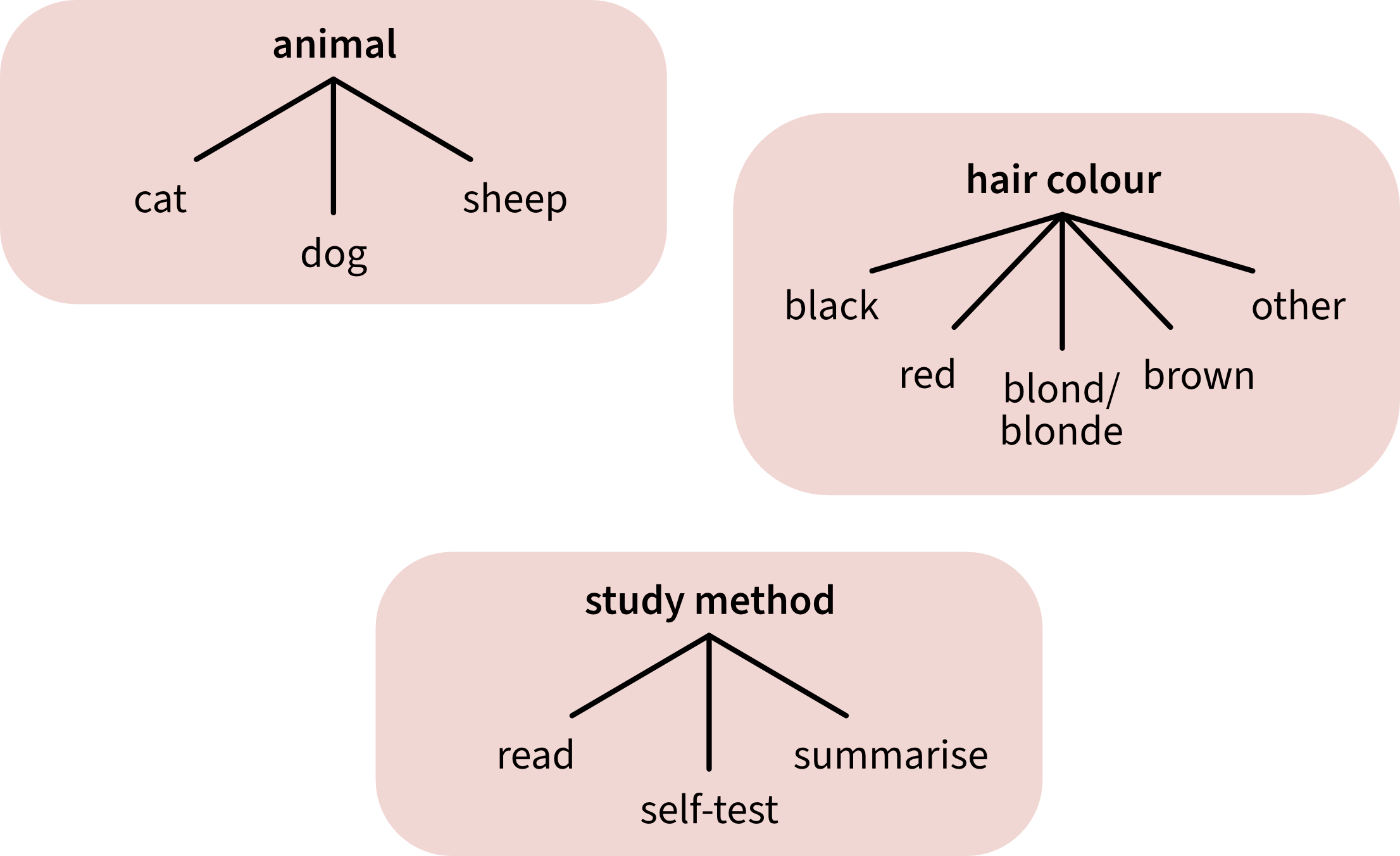

Examples of categorical predictors with >2 levels

Today’s data: Study method

How do we fit a line to data from three groups?

- It’s impossible to draw one single straight line through all three group means.

- The smallest number of straight lines that connect all three group means is two.

- For this reason, we’re going to use two predictors. These two predictors are called “dummy variables”.

- In general, for a categorical predictor with \(k\) levels, we’ll use \(k-1\) dummy variables.

Dummy variables let us extend dummy/treatment coding to >2 levels

Both dummy variables have the same reference level: read.

- The first dummy variable will compare

self-testback toread. - The second dummy variable will compare

summariseback toread.

Dummy variables let us extend dummy/treatment coding to >2 levels

First dummy variable: self-test vs. read.

Second dummy variable: summarise vs. read.

- Is the slope of the first dummy variable positive or negative?

- Is the slope of the second dummy variable positive or negative?

- Is the slope of the first dummy variable bigger than the slope of the second dummy variable?

- Is the intercept of the first dummy variable bigger than the intercept of the second dummy variable?

How do we know that a model will use these particular dummy variables?

The function contrasts() shows us how a categorical predictor will be coded.

(You’ll get error messages if the variable is not stored as a factor.)

How to read this output:

- Each column contains one dummy variable.

self-testcomparesself-test(the 1 in that column) toread.summarisecomparessummarise(the 1 in that column) toread.

- We know that the reference level is

readbecause in BOTH dummy variables,readis coded as 0.

Now is a good time for questions!

Modelling score ~ method

The linear expression:

\[ \text{score}_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (\beta_2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}}) + \epsilon_i \]

In R:

Call:

lm(formula = score ~ method, data = score_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-23.414 -5.359 -0.196 5.750 17.804

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.414 0.866 27.03 <2e-16 ***

methodself-test 4.162 1.319 3.16 0.0018 **

methodsummarise 0.782 1.193 0.66 0.5127

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 8.08 on 247 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.0422, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0345

F-statistic: 5.45 on 2 and 247 DF, p-value: 0.00484What does each coefficient mean? (1)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.414 0.866 27.03 <2e-16 ***

methodself-test 4.162 1.319 3.16 0.0018 **

methodsummarise 0.782 1.193 0.66 0.5127 What hypothesis is the model testing here?

- Null hypothesis: The mean score for the reference level (

read) is equal to zero. - \(p\)-value: the probability of observing an intercept of 23.414, assuming that the true intercept is zero.

Can we reject this null hypothesis?

If we care about differences between study methods, is this null hypothesis interesting?

What does each coefficient mean? (2)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.414 0.866 27.03 <2e-16 ***

methodself-test 4.162 1.319 3.16 0.0018 **

methodsummarise 0.782 1.193 0.66 0.5127 methodself-test aka \(\beta_1\): The difference between the mean score of self-test and the mean score of read.

What hypothesis is the model testing here?

- Null hypothesis: The difference between the mean score of

self-testand the mean score ofreadis equal to zero. - \(p\)-value: the probability of observing a difference of 4.162, assuming that the true difference is zero.

Can we reject this null hypothesis?

If we care about differences between study methods, is this null hypothesis interesting?

What does each coefficient mean? (3)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.414 0.866 27.03 <2e-16 ***

methodself-test 4.162 1.319 3.16 0.0018 **

methodsummarise 0.782 1.193 0.66 0.5127 methodsummarise aka \(\beta_2\): The difference between the mean score of summarise and the mean score of read.

What hypothesis is the model testing here?

- Null hypothesis: The difference between the mean score of

summariseand the mean score ofreadis equal to zero. - \(p\)-value: the probability of observing a difference of 0.782, assuming that the true difference is zero.

Can we reject this null hypothesis?

If we care about differences between study methods, is this null hypothesis interesting?

Now is a good time for questions!

What if we want to test other hypotheses?

What if we want to test other hypotheses?

For example, what if we want to know about how the two non-reference levels self-test and summarise are different from each other?

That hypothesis isn’t one of the hypotheses tested by the model.

The solution: use our old friend emmeans, “Estimated Marginal Means”.

- “Estimated” \(\rightarrow\) based on a model’s estimates

- “Marginal” \(\rightarrow\) for each level of a predictor, with the other predictors held constant

- “Means” \(\rightarrow\) averages (and confidence intervals!) of the estimated outcomes for each level of the predictor

Intro to testing hypotheses with emmeans

- Get estimated marginal means and 95% CIs for each level of the predictor. (This is as far as we got last time.)

Intro to testing hypotheses with emmeans

- Using these estimated marginal means and 95% CIs, we can compare any two levels of the predictor that we want. (This comparison is one example of “testing our own contrasts”—more details next week!)

2.1. We need to know the order of levels in the categorical predictor.

2.2. For every contrast you want to test, assign 1 to the level you’re interested in and -1 to the level you want to compare it to, using the level order above.

These comparisons will compute the level coded as 1 minus the level coded as –1.

We’ll test the significance of each of those differences.

Intro to testing hypotheses with emmeans

2.3. Use contrast() to find the \(p\)-value for each contrast.

contrast estimate SE df t.ratio p.value

self-test vs. read 4.16 1.32 247 3.156 0.0020

summarise vs. read 0.78 1.19 247 0.656 0.5130

self-test vs. summarise 3.38 1.29 247 2.622 0.0090These estimates look familiar:

When would you test your own contrasts using emmeans?

Testing our own contrasts using emmeans is not necessary for every analysis.

But it is useful if the hypotheses we want to test are not the same hypotheses that our a priori contrast coding (e.g., our dummy coding) will test.

Now is a good time for questions!

Changing the reference level

Changing the reference level

Another prediction activity:

Before, the reference level of method was read, and the non-reference levels were self-test and summarise.

Now, the reference level of method is summarise, and the non-reference levels are read and self-test.

- Would you expect the model coefficients to be the same or different?

- Would you expect the p-values of each model coefficient to be the same or different?

- Would you expect the estimated marginal means to be the same or different?

Predict: Write down your guesses about each question.

Explain: Why do you think your guesses are likely to be correct?

We’ll work through the example and you can check your predictions after.

How to change reference level in R?

The original dummy variables:

Re-code method, setting the base to our desired reference level (the third level of the variable).

Understanding the new dummy variables

First new dummy variable:

read vs. summarise.

Second new dummy variable:

self-test vs. summarise.

- Is the slope of the first dummy variable positive or negative?

- Is the slope of the second dummy variable positive or negative?

- Will the coefficient estimates be the same or different compared to our previous model?

New model vs. old model

Reference level = summarise (new).

Call:

lm(formula = score ~ method, data = score_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-23.414 -5.359 -0.196 5.750 17.804

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 24.196 0.820 29.50 <2e-16 ***

methodread -0.782 1.193 -0.66 0.5127

methodself-test 3.380 1.289 2.62 0.0093 **

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 8.08 on 247 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.0422, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0345

F-statistic: 5.45 on 2 and 247 DF, p-value: 0.00484Reference level = read (old).

Call:

lm(formula = score ~ method, data = score_data)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-23.414 -5.359 -0.196 5.750 17.804

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 23.414 0.866 27.03 <2e-16 ***

methodself-test 4.162 1.319 3.16 0.0018 **

methodsummarise 0.782 1.193 0.66 0.5127

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 8.08 on 247 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.0422, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0345

F-statistic: 5.45 on 2 and 247 DF, p-value: 0.00484In the summarise model (m3, on the left), what hypotheses are being tested for each coefficient?

Changing the reference level: emmeans

Are the estimated marginal means and 95% CIs from each model the same or different?

What difference does it make to change the reference level?

When the reference level of method is summarise, instead of read:

- The model coefficients are different.

- The set of hypotheses that the model tests are different.

- The estimated marginal means are the same.

Observe: Did your guesses match these results?

Explain: Why are the results the way they are?

Building an analysis workflow

Revisiting this week’s learning objectives

How can we include categorical variables as predictors in a linear model?

- Represent the variable numerically, for example using dummy coding (also called treatment coding).

- In dummy coding, the reference level (also called baseline level) is represented (“coded”) as 0, and the non-reference level is coded as 1.

- For categorical predictors with >2 levels, dummy coding uses “dummy variables” to individually compare each non-reference level to the same reference level.

When we use a categorical predictor, how do we interpret the linear model’s coefficients?

- Intercept (also written as \(\beta_0\)): The mean outcome for the reference level.

- Slope (also written as \(\beta_1\), \(\beta_2\), etc., or for short, \(\beta_j\)): The difference between (1) the mean outcome for the non-reference level and (2) the mean outcome for the reference level (when all other predictors are at zero).

Revisiting this week’s learning objectives

What hypotheses are tested by the default way that R represents categorical predictors?

- By default, R uses dummy coding/treatment coding. And by default, the reference level is the level that comes first in the alphabet.

- The intercept’s hypothesis test: The mean outcome for the reference level is different from zero.

- The slope’s hypothesis test: The difference between the (1) mean outcome for the non-reference level and (2) the mean outcome for the reference level is different from zero.

If we wanted to test different hypotheses after fitting the model, how might we do that?

- We can use a linear model to estimate what we’d expect our outcome variable to be for every value of our predictor(s).

- These expected outcome values are called “expected marginal means”.

- By comparing expected marginal means after fitting the model, we can test basically any hypotheses we want.

This week

Tasks

Attend your lab and work together on the exercises

Support

Help each other on the Piazza forum

Complete the weekly quiz

Attend office hours (see Learn page for details)

Appendix

Prediction equations: score ~ study

(two levels)

The linear expression that the model assumes has generated each data point \(i\) (the reference level is alone:

\[ score_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot study) + \epsilon_i \]

A little hat over the variable means that that’s an estimated value, so the model will estimate:

\[ \widehat{score} = \hat{\beta_0} + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot study) \]

With simple algebra, we can work out how the \(\beta\) coefficients relate to the estimated score of each group.

Studying alone is represented as study = 0.

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{score}_{alone} &= \hat{\beta_0} + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot study) \\ \widehat{score}_{alone} &= \hat{\beta_0} + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot 0) \\ \widehat{score}_{alone} &= \hat{\beta_0} + 0 \\ \widehat{score}_{alone} &= \hat{\beta_0} \\ \end{align} \]

Studying with others is represented as study = 1.

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{score}_{others} &= \hat{\beta_0} + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot study) \\ \widehat{score}_{others} &= \hat{\beta_0} + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot 1) \\ \widehat{score}_{others} &= \hat{\beta_0} + \hat{\beta_1} \\ \end{align} \]

Prediction equations: score ~ method

(three levels)

The linear expression that the model assumes has generated each data point \(i\) (the reference level is read):

\[ score_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\beta_2 \cdot method_{summarise}) + \epsilon_i \]

A little hat over the variable means that that’s an estimated value, so the model will estimate:

\[ \widehat{score} = \beta_0 + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \]

With simple algebra and with the help of the contrasts() function, we can work out how the \(\beta\) coefficients relate to the estimated score of each group.

First: Studying by reading is represented as \(method_{self-test} = 0\) and \(method_{summarise} = 0\). We get these numbers from the read row of the contrast matrix from contrasts().

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{score}_{read} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \\ \widehat{score}_{read} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot 0) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot 0) \\ \widehat{score}_{read} &= \hat{\beta_0} + 0 + 0 \\ \widehat{score}_{read} &= \hat{\beta_0} \\ \end{align} \]

Prediction equations: score ~ method

(three levels)

The linear expression that the model assumes has generated each data point \(i\) (the reference level is read):

\[ score_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\beta_2 \cdot method_{summarise}) + \epsilon_i \]

A little hat over the variable means that that’s an estimated value, so the model will estimate:

\[ \widehat{score} = \beta_0 + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \]

With simple algebra and with the help of the contrasts() function, we can work out how the \(\beta\) coefficients relate to the estimated score of each group.

Second: Studying by self-testing is represented as \(method_{self-test} = 1\) and \(method_{summarise} = 0\). We get these numbers from the self-test row of the contrast matrix from contrasts().

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{score}_{self} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \\ \widehat{score}_{self} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot 1) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot 0) \\ \widehat{score}_{self} &= \hat{\beta_0} + \hat{\beta_1} + 0 \\ \widehat{score}_{self} &= \hat{\beta_0} + \hat{\beta_1}\\ \end{align} \]

Prediction equations: score ~ method

(three levels)

The linear expression that the model assumes has generated each data point \(i\) (the reference level is read):

\[ score_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\beta_2 \cdot method_{summarise}) + \epsilon_i \]

A little hat over the variable means that that’s an estimated value, so the model will estimate:

\[ \widehat{score} = \beta_0 + (\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \]

With simple algebra and with the help of the contrasts() function, we can work out how the \(\beta\) coefficients relate to the estimated score of each group.

Third: Studying by summarising is represented as \(method_{self-test} = 0\) and \(method_{summarise} = 1\). We get these numbers from the summarise row of the contrast matrix from contrasts().

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{score}_{summ} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot method_{self-test}) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot method_{summarise}) \\ \widehat{score}_{summ} &= \hat{\beta_0} +(\hat{\beta_1} \cdot 0) + (\hat{\beta_2} \cdot 1) \\ \widehat{score}_{summ} &= \hat{\beta_0} + 0 + \hat{\beta_2} \\ \widehat{score}_{summ} &= \hat{\beta_0} + \hat{\beta_2} \\ \end{align} \]

Calculating marginal means by hand

For the score ~ method model with read as the reference level, the linear expression our linear expression is

\[ \text{score}_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (\beta_2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}}) + \epsilon_i \]

With the \(\beta\)s that the model estimated for us, we can compute the model’s predicted mean outcome for each group (aka, the estimated marginal means) by hand.

From the model summary, we know that

- \(\beta_0\) = 23.4

- \(\beta_1\) = 4.2

- \(\beta_2\) = 0.8

Substituting those values in, we get:

\[ \widehat{\text{score}} = 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (0.8 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}}) \]

Calculating marginal means by hand:

method = read

For method = read (first row of contrast matrix), we know that

- \(\text{method}_{\text{self-test}}\) = 0 (first column of the contrast matrix)

- \(\text{method}_{\text{summarise}}\) = 0 (second column of the contrast matrix)

Substituting those values in, we get:

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{read}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (0.8 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}})\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{read}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot 0) + (0.8 \cdot 0)\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{read}} &= 23.4\\ \end{align} \]

Thus the mean score when method = read should be 23.4—and it is.

Calculating marginal means by hand:

method = self-test

For method = self-test (second row of contrast matrix), we know that

- \(\text{method}_{\text{self-test}}\) = 1 (first column of the contrast matrix)

- \(\text{method}_{\text{summarise}}\) = 0 (second column of the contrast matrix)

Substituting those values in, we get:

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (0.8 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}})\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot 1) + (0.8 \cdot 0)\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + 4.2\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 27.6\\ \end{align} \]

Thus the mean score when method = self-test should be 27.6—and it is.

Calculating marginal means by hand:

method = summarise

For method = summarise (third row of contrast matrix), we know that

- \(\text{method}_{\text{self-test}}\) = 0 (first column of the contrast matrix)

- \(\text{method}_{\text{summarise}}\) = 1 (second column of the contrast matrix)

Substituting those values in, we get:

\[ \begin{align} \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{self-test}}) + (0.8 \cdot \text{method}_{\text{summarise}})\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + (4.2 \cdot 0) + (0.8 \cdot 1)\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 23.4 + 0.8\\ \widehat{\text{score}}_{\text{self-test}} &= 24.2\\ \end{align} \]

Thus the mean score when method = summarise should be 24.2—and it is.

Why bother with a reference level?

Why can’t we just compare each group individually to the overall mean?

Such a model might look something like this:

\[ score_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot read) + (\beta_2 \cdot selftest) + (\beta_3 \cdot summarise) + \epsilon_i \]

Each score is given by an intercept plus the difference between that intercept and each group’s scores. The mean \(\mu\) of each group would be:

\[ \begin{align} \mu_{read} &= \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot read)\\ \mu_{selftest} &= \beta_0 + (\beta_2 \cdot selftest)\\ \mu_{summarise} &= \beta_0 + (\beta_3 \cdot summarise)\\ \end{align} \]

For technical reasons, we cannot model this data this way.

We are trying to estimate three group means: \(\mu_{read}\), \(\mu_{selftest}\), \(\mu_{summarise}\). And for mathematical reasons, that means we can only have three parameters in our model. But the model above has four: \(\beta_0\), \(\beta_1\), \(\beta_2\), \(\beta_3\).

In technical terms, we say the model above is overparameterised.

Dummy coding with a reference level is one way to achieve three parameters for three group means: one intercept for the reference level and two differences between groups for the other two levels.

And we use emmeans to get any comparisons we want, regardless of a priori coding scheme.

Why does it matter which level is coded as 0

and which level is coded as 1?

Predict individually: Write down your guesses:

- The line’s intercept will be the same as the mean of either alone or others. Which one? Why?

- Will the slope of the line be positive or negative? Why?

Explain in pairs/threes: Why do you think your guesses are likely to be correct?

Why does it matter which level is coded as 0

and which level is coded as 1?

Predict individually: Write down your guesses:

- The line’s intercept will be the same as the mean of either alone or others. Which one? Why?

- Will the slope of the line be positive or negative? Why?

Explain in pairs/threes: Why do you think your guesses are likely to be correct?

Observe: Did your guesses match these results?

Explain: Why are the results the way they are?

How do we describe this line?

Using our mathematical toolkit:

\[ \text{score}_i = \beta_0 + (\beta_1 \cdot \text{study}) + \epsilon_i \]

\(\beta_0\): intercept, mean of alone (the level coded as 0):

\(\beta_1\): slope, the difference between mean of others (coded as 1) and mean of alone (coded as 0):

\(\epsilon_i\): error for each individual data point \(i\)