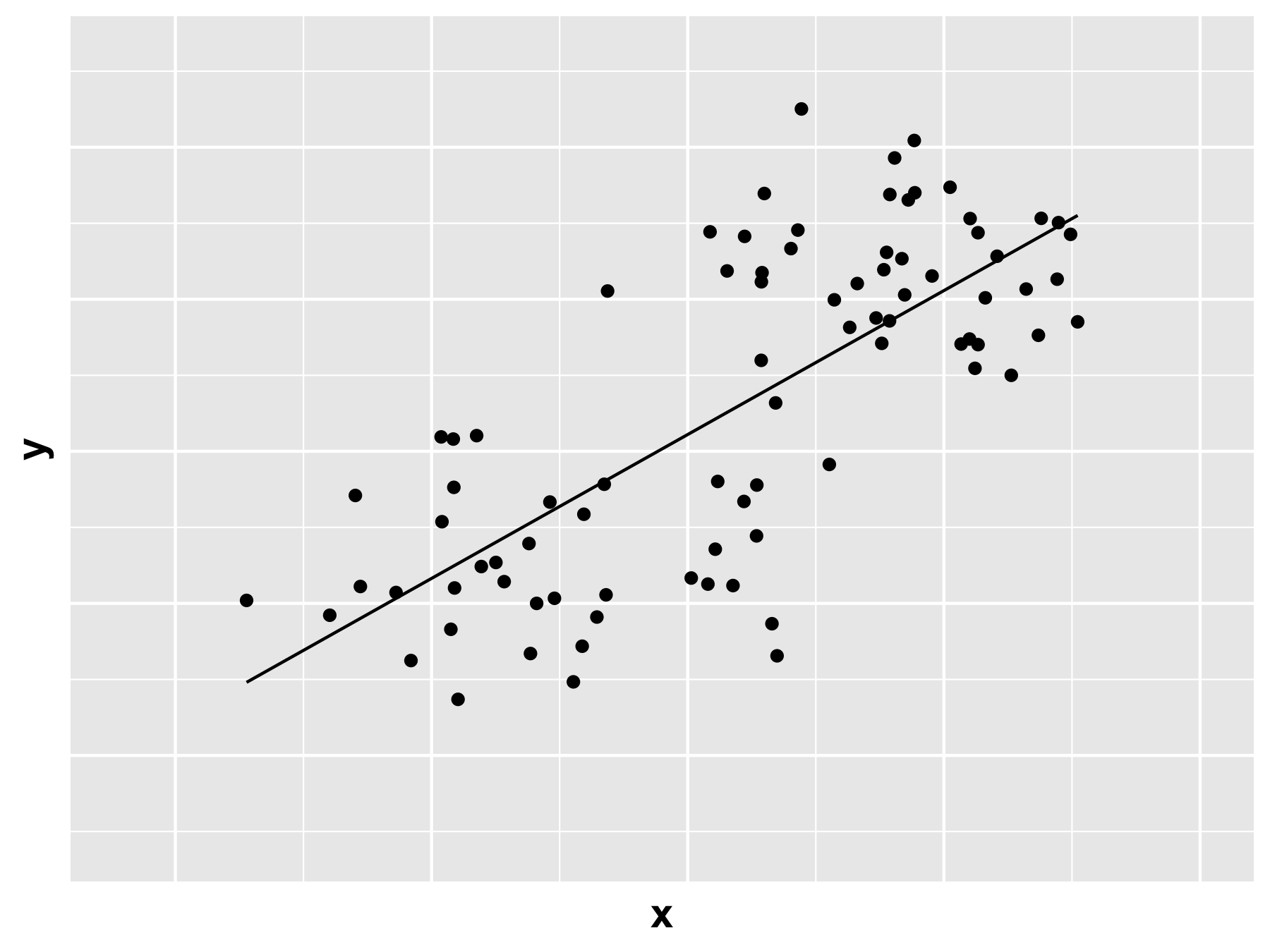

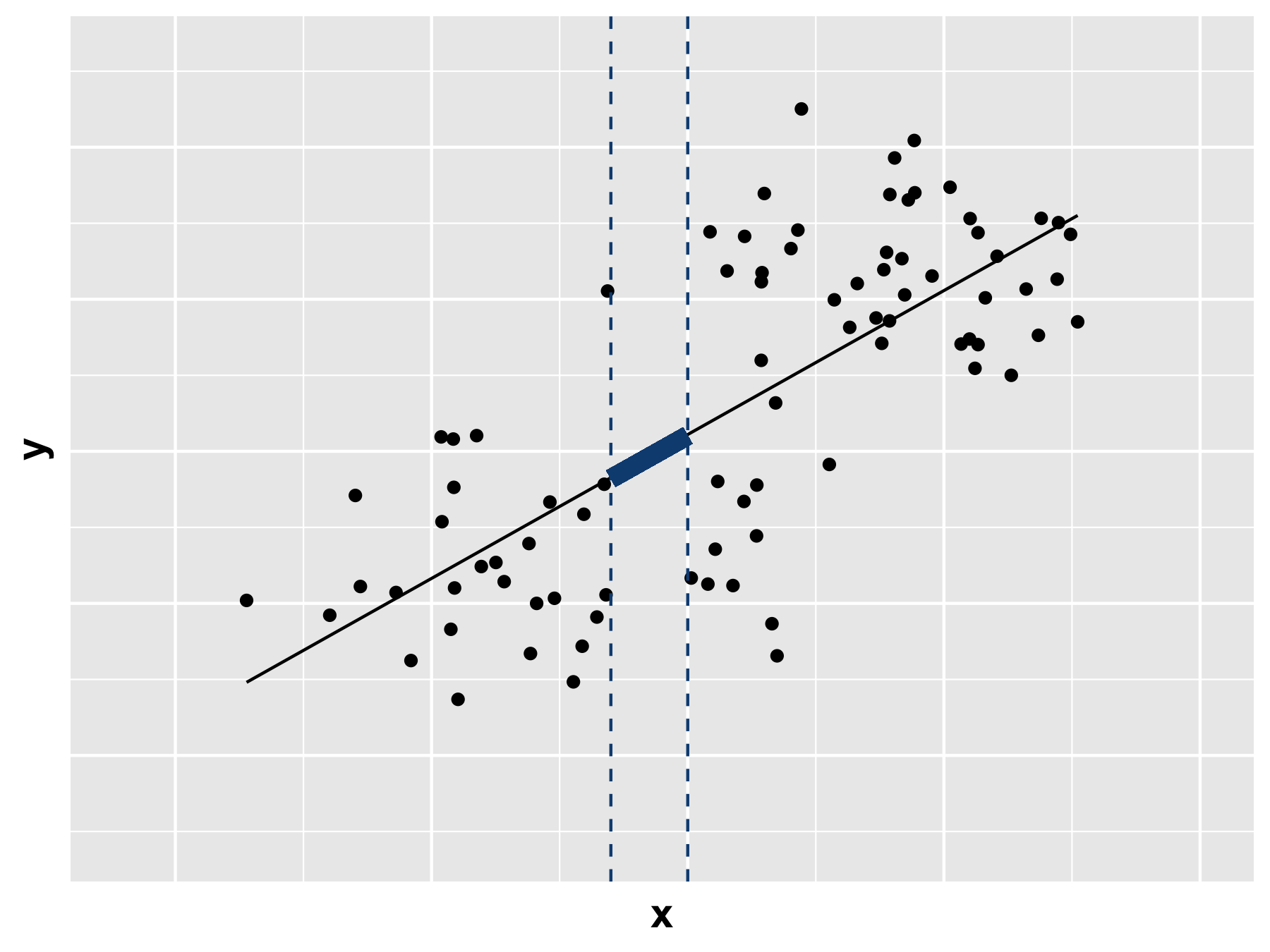

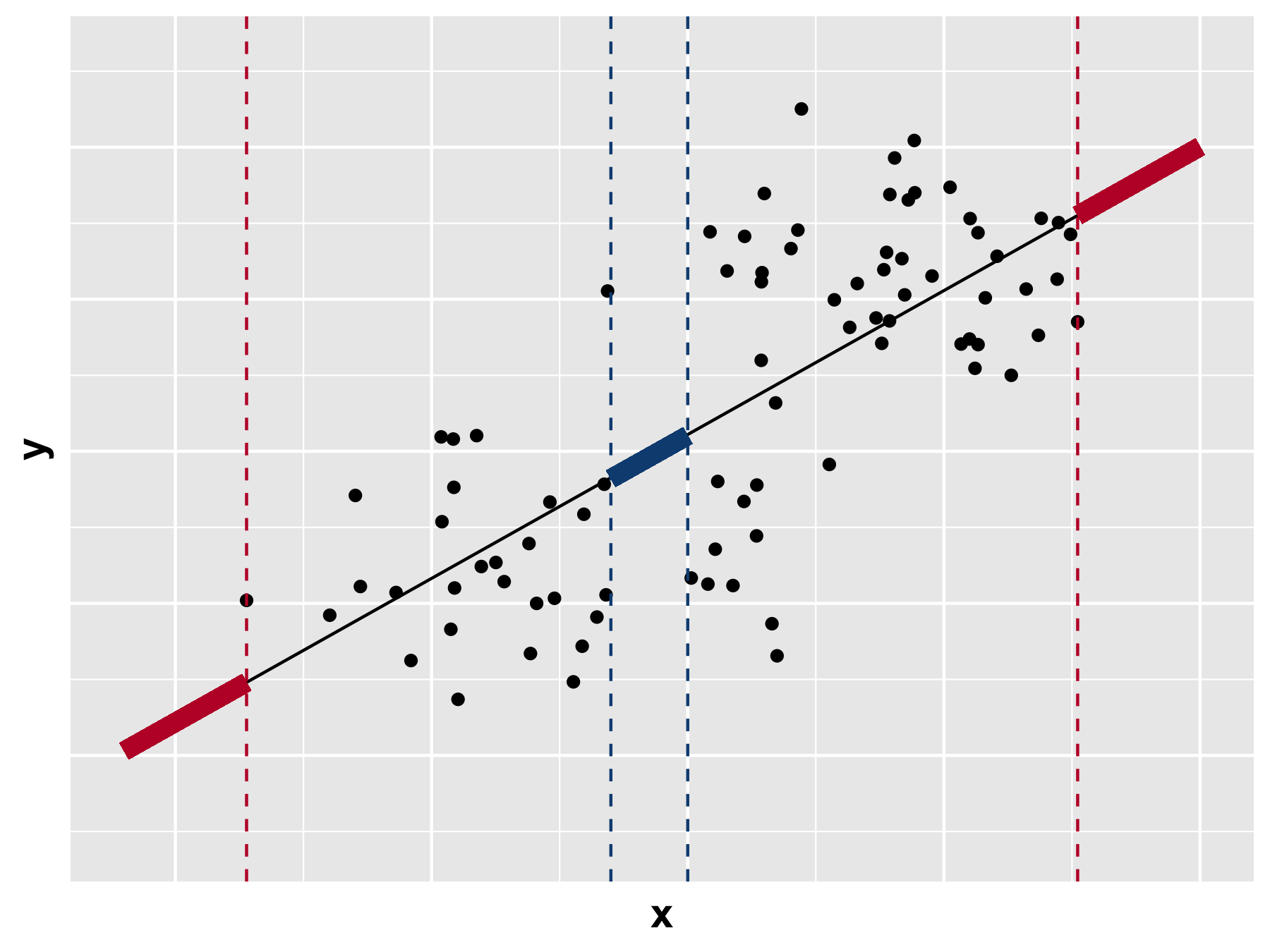

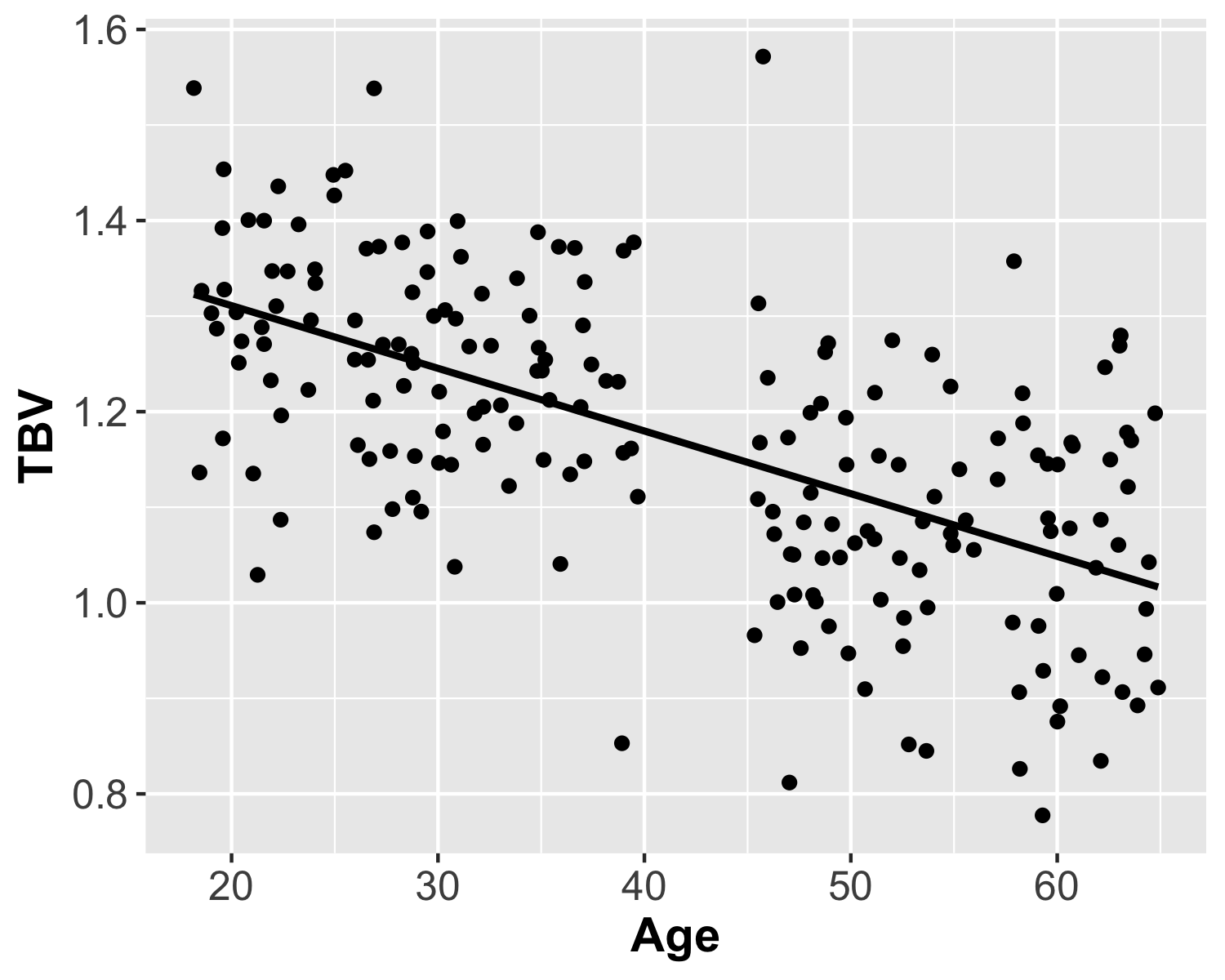

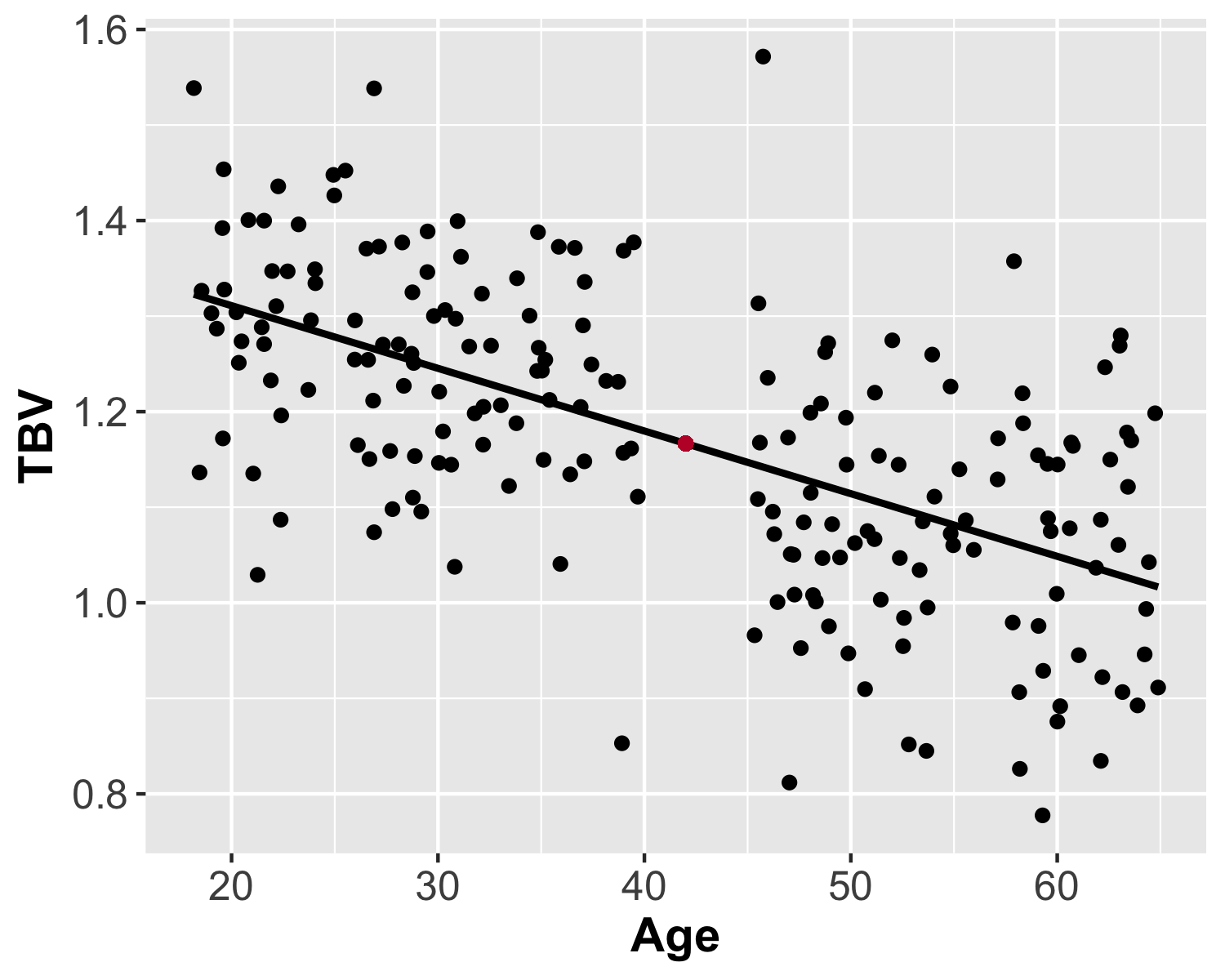

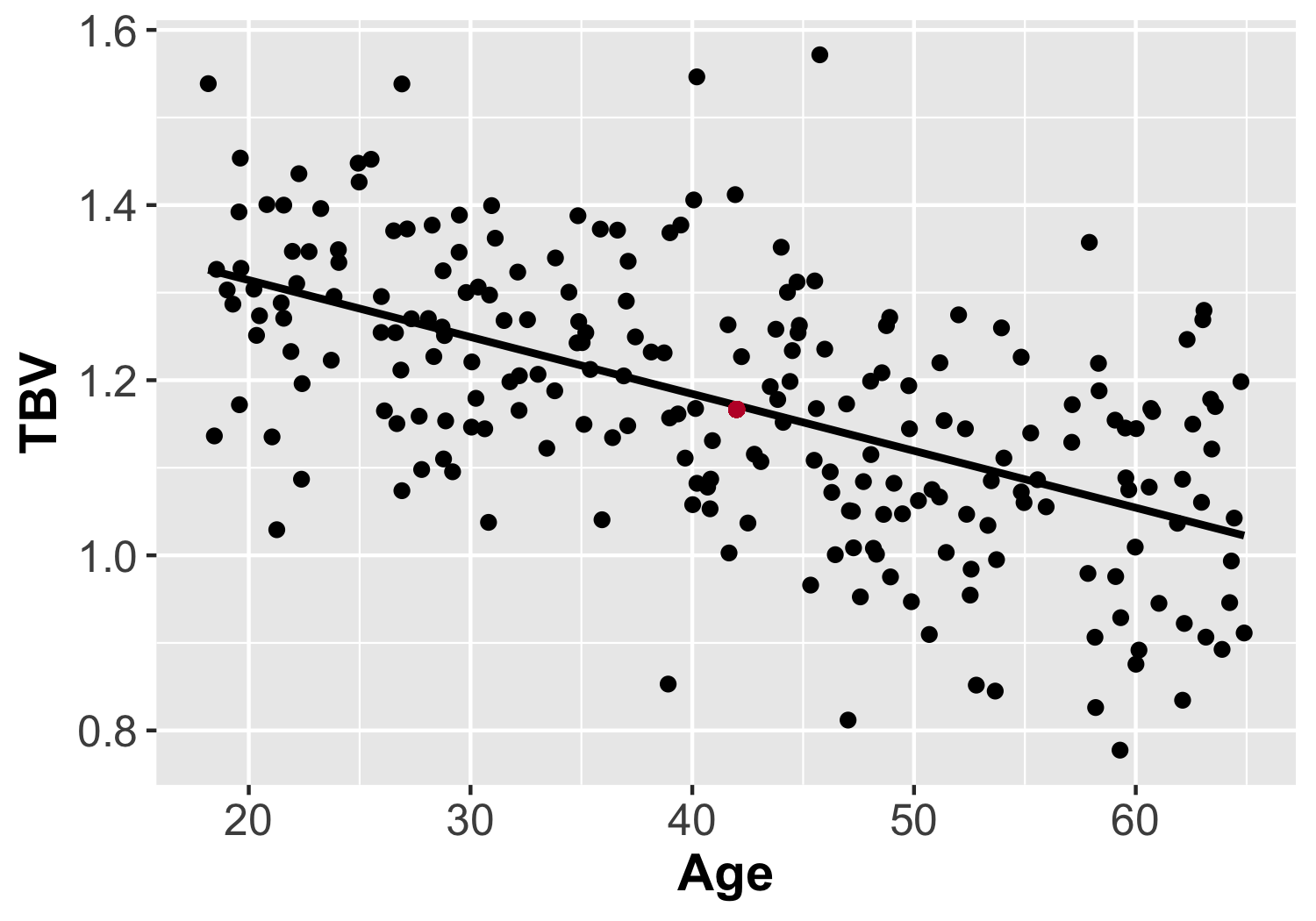

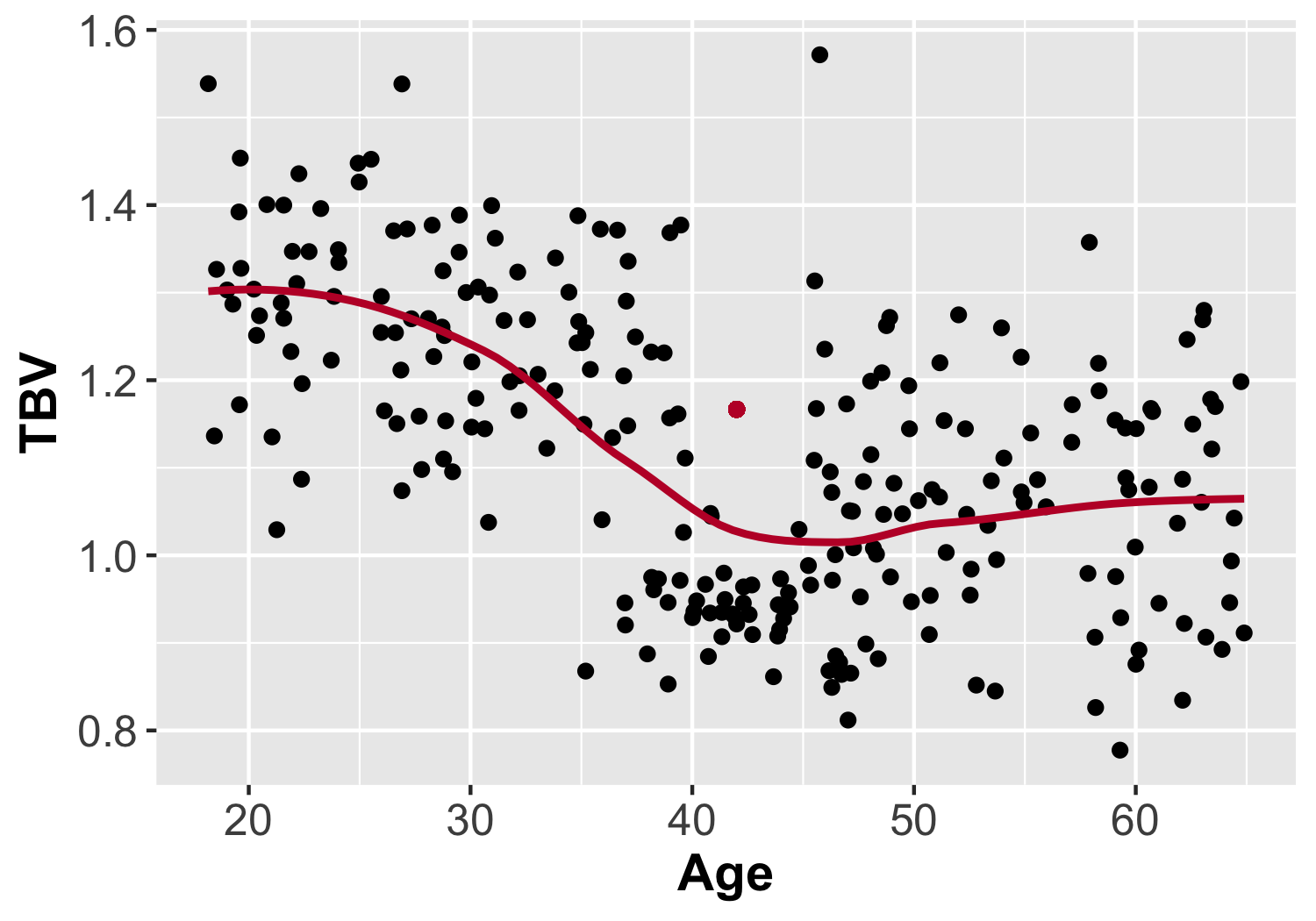

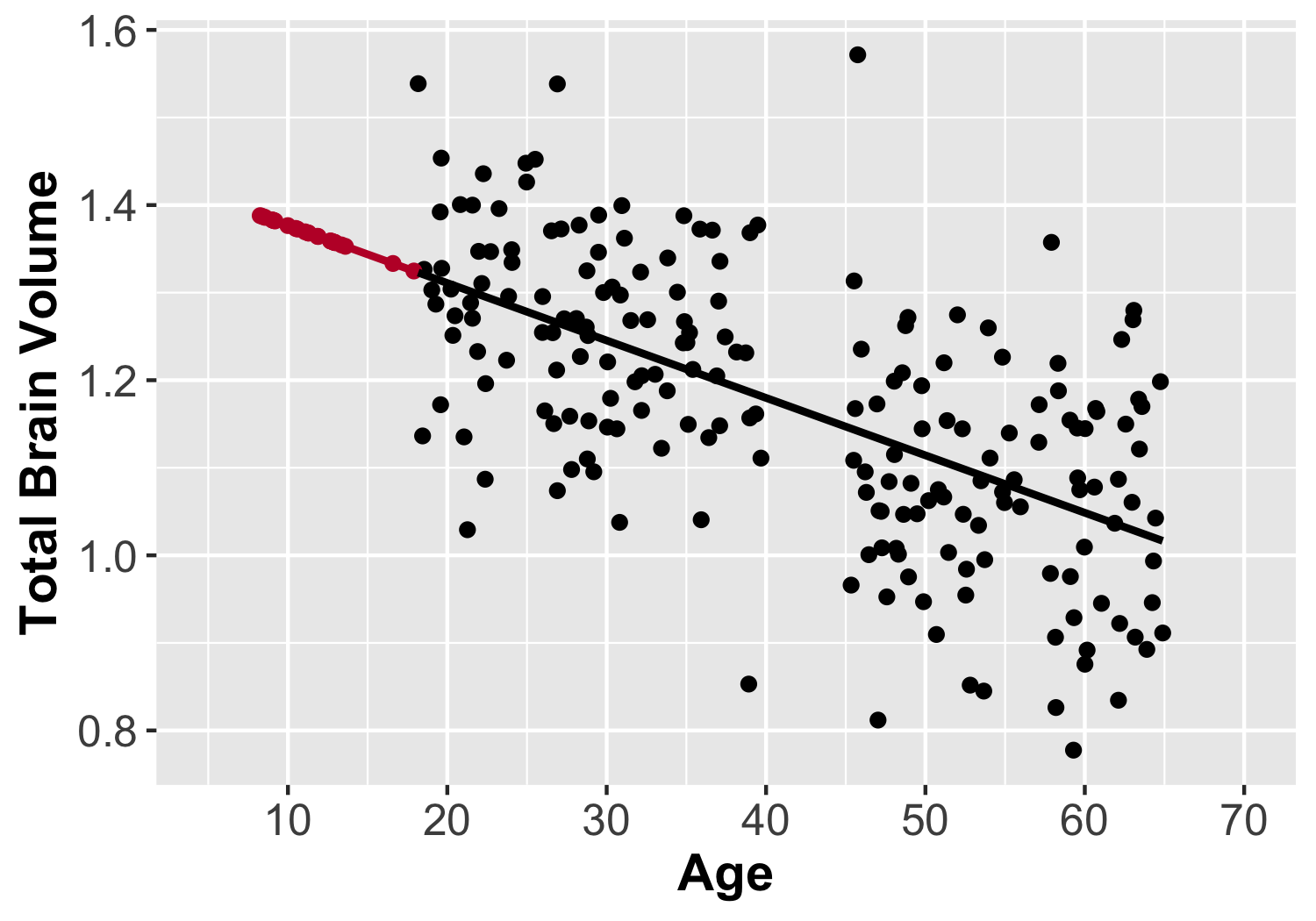

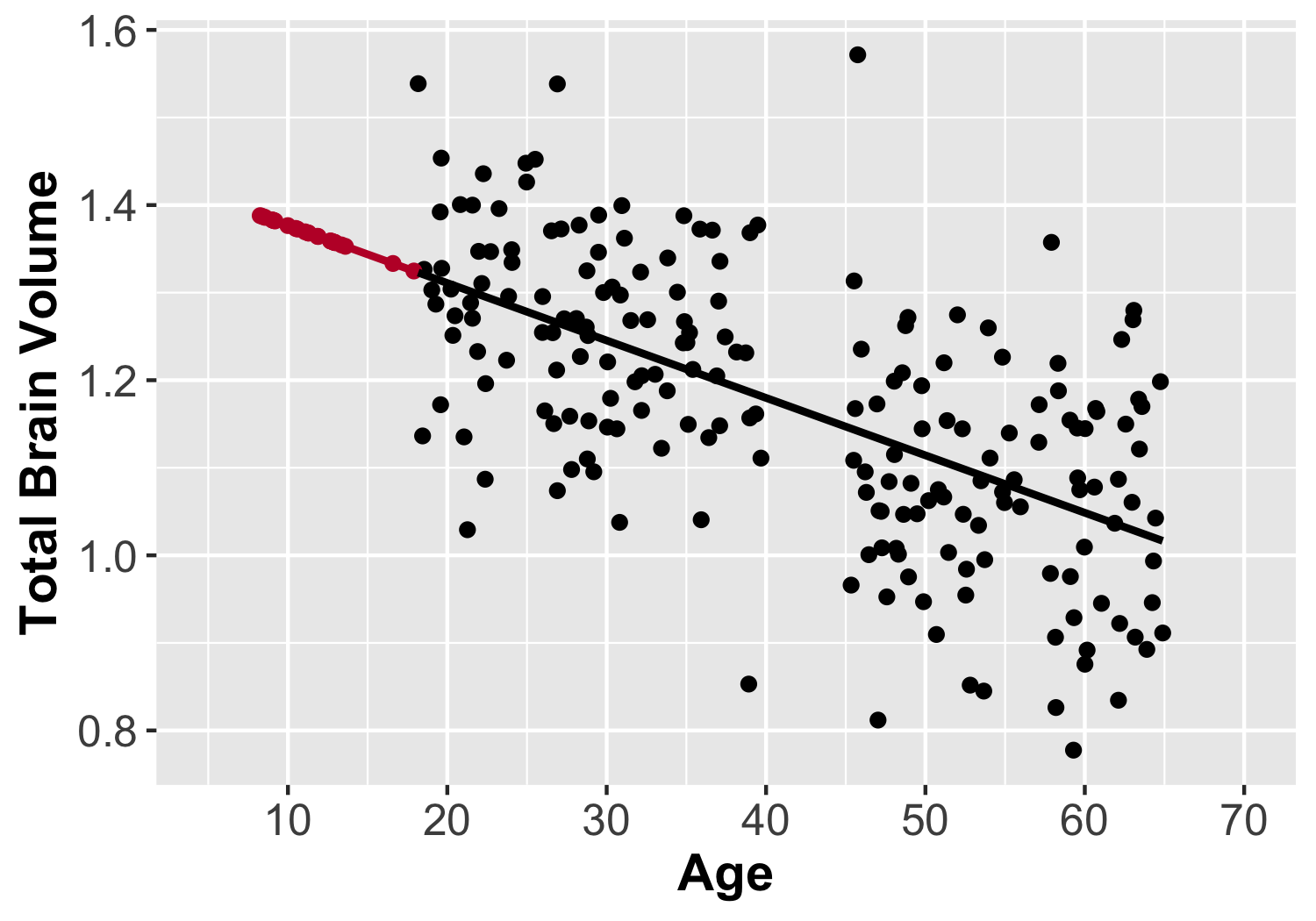

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # <b> Week 8: Understanding Linear Models </b> ] .subtitle[ ## Data Analysis for Psychology in R 2<br><br> ] .author[ ### dapR2 Team ] .institute[ ### Department of Psychology<br>The University of Edinburgh ] --- # Topics for the week + Causality + Conditions + Endogeneity + Prediction + Prediction vs Causality + Interpolation vs Extrapolation + Missing Data + Mechanisms of Missing Data + Possible Solutions --- # Why? + This lecture is about placing linear models in the broader context of science and study design + These are concepts you must consider when developing a research question, conducting analyses, and describing and interpreting your results + Important to understand what you can and cannot do with your model. --- class: inverse, center, middle # Part 1 ## Causality --- # Causality .pull-left[ + **Causality:** one event directly leads to another event + Sun exposure `\(\Rightarrow\)` sunburn + Note that this is different from **covariance**, where two variables change together ] --- count: false # Causality .pull-left[ + **Causality:** one event directly leads to another event + Sun exposure `\(\Rightarrow\)` sunburn + Note that this is different from **covariance**, where two variables change together .center[ <img src="./figs/sharkPlot.jpg" width="80%" /> ] ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Conditions for Causality + Covariation -- + Plausibility -- + Temporal Precedence + `\(A \Rightarrow B\)`, never `\(B \Rightarrow A\)` or `\(B \Leftrightarrow A\)` -- + No Reasonable Alternatives + Very hard to establish + Failing to account for alternative explanations may lead to spurious correlations --- # Conditions for Causality **Covariation** <span style="color: green;"> `\(\checkmark\)` </span> It is true that as ice cream purchases increase, so do shark attacks. ** `\(\oslash\)` ** However, you can buy ice cream, go for a swim, and fail to be attacked by a shark, or vice versa. -- **Plausibility** ** `\(\oslash\)` ** The idea of ice cream consumption directly causing a shark attack is not plausible. -- **Temporal Precedence** <span style="color: green;"> `\(\checkmark\)` </span> It's reasonable that the ice cream purchase always happens *before* the shark attack... -- **No Reasonable Alternatives** ** `\(\oslash\)` ** There is a much more logical explanation for the positive association between ice cream and shark attacks. --- # Testing Causality + Commonly, there is temptation to suggest causal relationships from linear models + Perhaps due to the nature of interpretation of coefficients -- ```r coef(lm(salary~service, salary)) ``` ``` ## (Intercept) service ## 14.277535 5.236961 ``` -- + This is often not reasonable. + Identifying causal relationships is often possible through careful study design rather than statistical testing --- # Testing Causality + We can try to measure causality by manipulating one variable and observing its effect on another + Experimental vs observational design -- + Most studies seek causal explanations from cross-sectional, correlational and observational studies. + Not impossible to make causal claims using observational data, but it's less straightforward + Propensity Score Matching; Instrumental Variable Analysis -- + Even in experimental studies, many are poorly designed. + Has to be a good theory of the causal-relation to test in the first place. --- # Endogeneity + Theoretically: Endogeneity occurs when the marginal distribution of a predictor variable is not independent of the conditional distribution of the outcome variable given the predictor variable. + *Marginal distribution* - an event's value independent of other events + *Conditional distribution* - an event's value given the value of another event -- + More practically: Endogeneity occurs when a predictor variable, `\(x\)`, is correlated with the error term ( `\(\epsilon\)` ) + `\(E(\epsilon|x) \not= 0\)` or `\(Cov(X,\epsilon) \not= 0\)` + When this happens, it will cause bias in the `\(\beta\)` estimates --- # Endogeneity + **Problem 1:** We can't easily test whether our variables are endogenous + Take a model with an endogenous variable, `\(x\)`, and an exogenous variable, `\(z\)`: + `\(y=\beta_0+\beta_1x + \beta_2z + \epsilon\)` + It seems as though we should be able to test for endogeneity by checking whether `\(Cov(x,\epsilon) \not= 0\)` + However, our model's estimate of `\(\epsilon\)` will be biased by the endogenous `\(x\)` variable -- + **Problem 2:** Even if you successfully identify endogeneity in your model, you must still determine *why* it's there in order to solve the problem --- # Sources of Endogeneity + Simultaneity Bias + Omitted/Confounding Variables + Measurement Error --- # Simultaneity Bias + Causality goes both ways + `\(x\)` causes `\(y\)`, which causes `\(x\)` + Example: `\(Farmer's\ Income \Leftrightarrow Crop\ Yield\)` + Consider the model, `\(y = \beta_0+\beta_1x_{ex} + \beta_2x_{en}\)` + If endogeneity is due to simultaneity, `\(x_{ex}\)` will lead to change in `\(y\)`, which will then lead to change in `\(x_{en}\)`. + With multiple endogenous variables, this effect would be even more pronounced. -- + **Solution** + Use statistical methods specifically developed for this situation (e.g., two-stage least squares regression) --- # Omitted/Confounding Variables .pull-left[ + In a perfectly exogenous model, the effect of `\(x\)` on `\(y\)` is separate from `\(\epsilon\)` + When `\(x\)` is correlated with both the outcome and an omitted variable `\(z\)`, the variance explained by `\(z\)` falls on `\(\epsilon\)` ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Exogenous Model** <img src="figs/SimpleLinearModel.png" width="35%" /> **Endogenous Model** <img src="figs/LinearMod_Endo.png" width="35%" /> ]] --- count: false # Omitted/Confounding Variables .pull-left[ + In a perfectly exogenous model, the effect of `\(x\)` on `\(y\)` is separate from `\(\epsilon\)` + When `\(x\)` is correlated with both the outcome and an omitted variable `\(z\)`, the variance explained by `\(z\)` falls on `\(\epsilon\)` + **Solution** + Ensure potential confounds are measured and included in model + No small task! + Requires a thorough knowledge of your research topic ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Exogenous Model** <img src="figs/SimpleLinearModel.png" width="35%" /> **Endogenous Model** <img src="figs/LinearMod_Endo.png" width="35%" /> ]] --- # Measurement Error .pull-left[ + Instead of measuring `\(x\)`, you measure `\(x^*\)`, which is a measurement of `\(x\)` with error ( `\(r\)` ) included. + Examples of measurement error: + Reporting Errors + Coding Errors + Similar to the case of omitted variables, measurement error becomes part of `\(\epsilon\)`, but will be associated with `\(x\)`, leading to endogeneity. ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Exogenous Model** <img src="figs/SimpleLinearModel.png" width="35%" /> **Endogenous Model** <img src="figs/LinearMod_Endo_measurement.png" width="35%" /> ]] --- count: false # Measurement Error .pull-left[ + Instead of measuring `\(x\)`, you measure `\(x^*\)`, which is a measurement of `\(x\)` with error ( `\(r\)` ) included. + Examples of measurement error: + Reporting Errors + Coding Errors + Similar to the case of omitted variables, measurement error becomes part of `\(\epsilon\)`, but will be associated with `\(x\)`, leading to endogeneity. + **Solutions** + Careful planning and study design + Pilot testing ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Exogenous Model** <img src="figs/SimpleLinearModel.png" width="35%" /> **Endogenous Model** <img src="figs/LinearMod_Endo_measurement.png" width="35%" /> ]] --- class: center, middle # Questions..... --- class: inverse, center, middle # Part 2 ## Prediction --- # Prediction + Understanding causality may be quite important when developing a theory, but prediction is more often emphasized in applied sciences. + Insurance companies likely don’t care *why* a particular person is a higher risk for fraudulent claims, they just want to know who those people are. + Marketing companies may not really care *why* some people buy certain brands, they just want to know who does. --- # Prediction + One of the aims of linear modeling is to produce a model to predict our outcome variable, `\(y\)` + Recall how we make predictions: + We measure our outcome, `\(y\)`, and a set of predictors, `\(x_1...x_i\)`, on a sample. + We run our model and get estimates for `\(\beta\)`(s). + We then plug these `\(\beta\)`s into our regression equation, along with values of the associated `\(x\)`s + We can do this not only for our sample, but for anyone else for which we have values for `\(x\)` + We can also do this for hypothetical values of `\(x\)` --- # Predicting Values Outwith the Original Dataset + When collecting data, the range of our sample's predictor and outcome variables may not span the full range of these variables as they exist in the world. + e.g., hours spent studying as a predictor of test performance + Knowing this, we can think about the prediction of two sets of unknown values: + Those within the range used to estimate the model + Those outside the range used to estimate the model --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- count: false # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-left[ + ** <span style="color: #0F4C81;">Interpolation:</span> ** Obtaining a value from a model within the range of given data or points ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- count: false # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-left[ + ** <span style="color: #0F4C81;">Interpolation:</span> ** Obtaining a value from a model within the range of given data or points + **Extrapolation:** Obtaining value from a model from outside the range of given points or data points. ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-left[ + Imagine you created a model that predicts total brain volume across the lifetime. + You collect data from participants aged 18-65, but somehow have no participants aged 40-45. ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Model Data** <!-- --> ] ] --- count: false # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-left[ + Imagine you created a model that predicts total brain volume across the lifetime. + You collect data from participants aged 18-65, but somehow have no participants aged 40-45. + What if you were to use your model to ** <span style="color: #0F4C81;">interpolate</span> ** the total brain volume of someone who is 42? ```r brainMod <- lm(TBV~Age, brainDat2) newDat <- data.frame(Age=42) predict(brainMod, newDat) ``` ``` ## 1 ## 1.166655 ``` ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Model Data** <!-- --> ] ] --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation + A value of 1.17 for a 42-year-old seems reasonable, given the observed pattern of measured data on either side of the predicted point. .pull-left[ .center[ **Likely** <!-- --> ] ] .pull-right[ .center[ **Less Likely** <!-- --> ] ] --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation + Now imagine you use your model to **extrapolate** the total brain volume across a group of 25 primary and secondary school students (ages 8-18). .pull-left[ ```r summary(studentDat) ``` ``` ## Age ## Min. : 8.258 ## 1st Qu.: 9.187 ## Median :11.302 ## Mean :11.541 ## 3rd Qu.:12.888 ## Max. :17.902 ``` ```r head(predict(brainMod, studentDat), 4) ``` ``` ## 1 2 3 4 ## 1.364349 1.376553 1.368210 1.382793 ``` ] .pull-right[ <!-- --> ] --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation .pull-left[ While these values appear reasonable, we don't have measured values on both sides to give us a sense of whether the pattern stays consistent. .center[ **Predicted Values** <!-- --> ] ] -- .pull-right[ In fact, the true nature of things looks more like this: <p> </p> .center[ **Actual <font size=2>(Simulated)</font> Values** <img src="figs/TBVbyAge.png" width="90%" /> ] ] --- # Interpolation vs Extrapolation + In general, extrapolation is **not recommended**, especially when the underlying trajectory of the data is unknown + If you choose to do so, you should extrapolate with extreme caution and provide explicit justification for why it is necessary and valid > "Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future" - Niels Bohr...or Yogi Berra. Or a Danish proverb. --- class: center, middle # Questions..... --- class: inverse, center, middle # Part 3 ## Missing Data --- # Missing Data + Missing data is very common + We worry about two main things with missing data: + Loss of efficiency (due to smaller sample size) + Bias (i.e., incorrect estimates) + The effects of missing data depend on a combination of the missing data mechanism and how we deal with the missing data --- # Missing Data + There can be several reasons for missing data: + Participant non-responses + Errors in data collection + Errors in data entry + Missing by design + Missing data can be of several types: + Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) + Missing at Random (MAR) + Missing Not at Random (MNAR) --- # MAR + Missing at random (MAR) means: **When the probability of missing data on a variable Y is related to other variables in the model but not to the values of Y itself** + Example: + X = self-control and Y = aggression. + People with lower self-control are more likely to have missing data on aggression. + After taking into account self-control, people who are high in aggression are no more likely to have missing data on aggression. + Challenge is that there is no way to confirm that there is no relation between aggression scores and missing data on aggression because that would require knowledge of the missing scores. --- # MCAR + Missing completely at random (MCAR) means: **Genuinely random missingness. No relation between Y or any other variable in the model and missingness on Y** + The data you have are a simple random sample of the complete data. + The ideal missing data scenario! + Example: + X = self-control and Y = aggression + People of all levels of self-control and aggression are equally likely to have missing data on aggression --- # MNAR + Missing not random (MNAR) means: **When the probability of missingness on Y is related to the values of Y itself** + Example: + X = self-control, Y = aggression + Those high in aggression are more likely to have missing data on the aggression variable, even after taking into account self-control. + As with MAR, there is no way to verify that data are MNAR without knowledge of the missing values --- # Methods for Missing Data + Deletion Methods + Listwise Deletion + Pairwise Deletion + Imputation Methods + Mean Imputation + Regression Imputation + Multiple Imputation + Maximum likelihood estimation + Methods for MNAR + Pattern mixture models + Random coefficient models --- # Deletion Methods + Listwise deletion or complete case analysis + Delete everyone from the analysis who has missing data on either self-control or aggression + Will give biased results unless data are MCAR + Even if data are MCAR, power will be reduced by reducing the sample size + Bottom line: **not recommended** --- # Deletion Methods + Pairwise deletion or available-case analysis + Uses available data for each analysis + Different cases contribute to different correlations in a correlation matrix + Example: + Cases 2,3,7,18, 56, 100 not used in the self-control- aggression correlation + Cases 2,7,18,77, 103 not used in the aggression-substance use correlation + Doesn’t reduce power as much as listwise deletion + But still gives biased results whenever data are not MCAR + Bottom line: **not recommended** --- # Mean Imputation + Replace missing values with the mean on that variable + Two major issues: + artificially reduces the variability of the data + can give very biased estimates even when data are MCAR + Bottom line: **not recommended** > ‘possibly the worst missing data handling method available… you should absolutely avoid this approach’ Enders (2011) --- # Regression Imputation - Replaces the missing values with values predicted from a regression - Estimate a set of regression equations where the incomplete variables are predicted from the complete variables - Use the regression equations to calculate the predicted values on the incomplete variables - Based on the principle of using information from the complete data to estimate the missing data - Two forms: - ‘normal’ regression imputation - Stochastic regression imputation (adds a residual term to overcome loss of variance) - Stochastic regression is preferred and gives unbiased results if data are MAR --- # Multiple Imputation - Procedure: - Imputes missing data several times to create multiple complete datasets - Analyses are conducted for each dataset - Analysis results are pooled across datasets to get parameter estimates and standard errors - 3-5 datasets are often enough but more is better and 20+ is ideal - Unlike in most single imputation approaches, the standard errors take account of the additional uncertainty due to missingness - Gives unbiased parameter estimates under MAR - Can be tedious if pooling has to be done by hand -Bottom line: **recommended method if data are likely to be MAR** - If using MI, include as many variables and higher-order effects as possible in the imputation phase --- # Maximum Likelihood Estimation - Estimation method - Makes use of all the information in the model to arrive at the parameter estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) ‘as if’ the data were complete - Does not ‘impute’ individual values - Gives unbiased estimates under MAR - Assumes multivariate normality - Even under MCAR it is superior to listwise and pairwise deletion because it uses more information from the observed data. - Practical advantage= easy to implement, usually much more so than multiple imputation - Bottom line: **recommended method if data are likely to be MAR** --- # Methods for MNAR - Selection models: - Combines model for predicting missingness as well as the analysis model of interest, e.g.: - Selection model= predict missingness on aggression from covariates such as gender, age, ADHD scores - Substantive model= predict aggression from self-control - The parameter estimates of the latter are adjusted by the inclusion of the former - Makes strong, untestable assumptions - Under many realistic conditions, gives worse results than MI or MLE, even when the MAR assumption is violated - Bottom line: **Good to include as part of a sensitivity analysis but often between to use MI or MLE** --- # Methods for MNAR - Pattern mixture models - Stratifies the sample according to different missing data patterns - E.g. pattern 1= complete data , pattern 2= ‘missing on aggression’ , pattern 3= ‘missing on self-control’ - Estimates the substantive model in each subgroup - Pools the results from each subgroup to get a weighted average parameter estimate - Similar to selection model, requires strong untestable assumptions - Violations of the assumptions lead to bias - Bottom line: **Good to include as part of a sensitivity analysis but often between to use MI or MLE** --- # What to do? .pull-left[ .center[ **When MLE may be better:**] - When the substantive model includes interactions - For structural equation models (more on this in dapR3) - For the inexperienced (easier to learn and implement) ] .pull-right[ .center[ **When MI may be better:**] - When a structural equation model has categorical indicators - When there is missing data on the predictors - When including auxiliary variables ] --- class: center, middle # Questions..... --- # Summary of This Week + Discussed conditions required for causality + Reviewed issues with determining causality (endogeneity) and potential solutions + Differentiated between predication and causality + Defined interpolation and extrapolation (and cautioned against extrapolating) + Provided an overview of missing data and the methods you may read about --- class: center, middle # Thanks for listening!