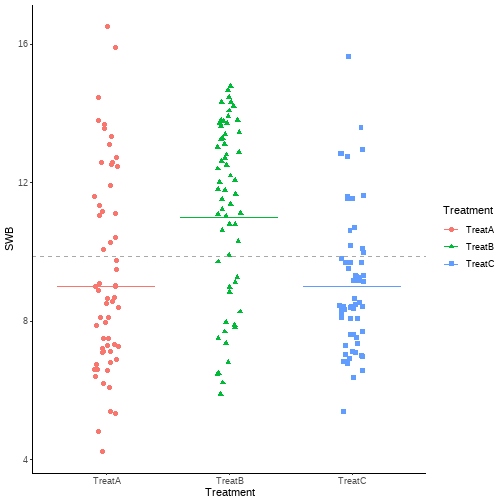

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # <b> Coding Categorical Data </b> ## Data Analysis for Psychology in R 2<br><br> ### dapR2 Team ### Department of Psychology<br>The University of Edinburgh --- # Weeks Learning Objectives 1. Interpret the output from a model using dummy coding. 2. Interpret the output from a model using sum-to-zero coding. 3. Create specific contrast matrices to test specific effects. 4. Understand the distinction between orthogonal and non-orthogonal contrasts. --- # Topics for today + Last time we looked at the `\(F\)`-test in one-way designs and linear models + This time we are going to consider contrasts and `\(\beta\)` coefficients --- # Looking beneath the F-test + The `\(F\)`-test gives us an overall test of the model, or the difference between two models. + And we saw we can apply this to seeing the overall effect of a categorical variable with 2+ levels. + But we may want to know something more specific. + Differences between specific groups or sets of groups. + In such cases we talk about... + contrasts & planned comparisons + *post-hoc test (not for today)* + So how do we approach these from the linear model perspective? --- # Contrasts and Planned comparisons + Sometimes we want to make comparisons between pairs of things. + Treatment A vs Treatment B + Treatment A vs (Treatment B & Treatment C) etc. + Such comparisons can be... + Specified a priori (confirmatory) + For all possible comparisons (exploratory) + We achieve these comparisons via assigning weights to groups. + May sound complicated, but we have already seen this practice in action this year --- # Dummy coding (reference group) + Create `\(k\)`-1 dummy variables/contrasts + where `\(k\)` is the number of levels of the categorical predictor. + Assign reference group 0 on all dummies. + Assign 1 to the focal group for a particular dummy. + Enter the dummies into the linear model and they code the difference in means between the focal group/level and the reference. --- # `Hospital` & `Treatment` data + **Condition 1**: `Treatment` (Levels: TreatA, TreatB, TreatC). + **Condition 2**: `Hospital` (Levels: Hosp1, Hosp2). + Total sample n = 180 (30 patients in each of 6 groups). + Between person design. + **Outcome**: Subjective well-being (`SWB`) + An average of multiple raters (the patient, a member of their family, and a friend). + SWB score ranged from 0 to 20. --- # The data ```r hosp_tbl <- read_csv("hospital.csv", col_types = "dff") hosp_tbl %>% slice(1:10) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 10 x 3 ## SWB Treatment Hospital ## <dbl> <fct> <fct> ## 1 6.2 TreatA Hosp1 ## 2 15.9 TreatA Hosp1 ## 3 7.2 TreatA Hosp1 ## 4 11.3 TreatA Hosp1 ## 5 11.2 TreatA Hosp1 ## 6 9 TreatA Hosp1 ## 7 14.5 TreatA Hosp1 ## 8 7.3 TreatA Hosp1 ## 9 13.7 TreatA Hosp1 ## 10 12.6 TreatA Hosp1 ``` --- # Why do we need a reference group? + Consider our example. + We have three groups each given a specific Treatment A, B or C + We want a model that represents our data (observations), but all we "know" is what group an observation belongs to. So; `$$y_{ij} = \mu_i + \epsilon_{ij}$$` + Where + `\(y_{ij}\)` are the individual observations + `\(\mu_i\)` is the mean of group `\(i\)` and + `\(\epsilon_{ij}\)` is the individual deviation from that mean. ??? + And this hopefully makes sense. + Given we know someone's group, our best guess is the mean + But people wont all score the mean, so there is some deviation for every person. --- # Why do we need a reference group? + An alternative way to present this idea looks much more like our linear model: `$$y_{ij} = \beta_0 + \underbrace{(\mu_{i} - \beta_0)}_{\beta_i} + \epsilon_{ij}$$` + Where + `\(y_{ij}\)` are the individual observations + `\(\beta_0\)` is an estimate of reference/overall average + `\(\mu_i\)` is the mean of group `\(i\)` + `\(\beta_1\)` is the difference between the reference and the mean of group `\(i\)`, and + `\(\epsilon_{ij}\)` is the individual deviation from that mean. --- # Why do we need a reference group? + We can write this equation more generally as: $$\mu_i = \beta_0 + \beta_i $$ + or for the specific groups (in our case 3): `$$\mu_{treatmentA} = \beta_0 + \beta_{1A}$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentB} = \beta_0 + \beta_{2B}$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentC} = \beta_0 + \beta_{3C}$$` + **The problem**: we have four parameters ( `\(\beta_0\)` , `\(\beta_{1A}\)` , `\(\beta_{2B}\)` , `\(\beta_{3C}\)` ) to model three group means ( `\(\mu_{TreatmentA}\)` , `\(\mu_{TreatmentB}\)` , `\(\mu_{TreatmentC}\)` ) + We are trying to estimate too much with too little. + This is referred to as under-identification. + We need to estimate at least 1 parameter less --- # Constraints fix identification + Consider dummy coding. + Suppose we make Treatment A the reference. Then, `$$\mu_{treatmentA} = \beta_0$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentB} = \beta_0 + \beta_{2B}$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentC} = \beta_0 + \beta_{3C}$$` + Fixed! + We now only have three parameters ( `\(\beta_0\)` , `\(\beta_{2B}\)` , `\(\beta_{3C}\)` ) for the three group means ( `\(\mu_{TreatmentA}\)` , `\(\mu_{TreatmentB}\)` , `\(\mu_{TreatmentC}\)` ). --- # Group Means ```r hosp_tbl %>% select(1:2) %>% group_by(Treatment) %>% summarise( mean = round(mean(SWB),3), sd = round(sd(SWB),1), N = n() ) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 4 ## Treatment mean sd N ## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> ## 1 TreatA 9.33 2.9 60 ## 2 TreatB 11.3 2.5 60 ## 3 TreatC 9.04 2 60 ``` --- # Dummy (reference) model ```r summary(lm(SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -5.373 -1.987 -0.300 1.838 7.173 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 9.3267 0.3242 28.770 < 2e-16 *** ## TreatmentTreatB 1.9467 0.4585 4.246 3.51e-05 *** ## TreatmentTreatC -0.2850 0.4585 -0.622 0.535 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 2.511 on 177 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.1369, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1271 ## F-statistic: 14.04 on 2 and 177 DF, p-value: 2.196e-06 ``` --- # Dummy (reference) model .pull-left[ ``` ## (Intercept) TreatmentTreatB TreatmentTreatC ## 9.327 1.947 -0.285 ``` + Recall the equations for the group means: `$$\mu_{treatmentA} = \beta_0$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentB} = \beta_0 + \beta_1$$` `$$\mu_{treatmentC} = \beta_0 + \beta_2$$` ] .pull-right[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Treatment </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> mean </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.327 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatB </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11.273 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatC </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.042 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- class: center, middle # Time for a break **Take a little time to look back over dummy coding to make sure you feel happy with the key principles** --- class: center, middle # Welcome Back! **Now we are going to look at some other options to dummy coding** --- # Why not always use dummy coding? + We might not always want to compare against a reference group. + We might want to compare to: + The overall or grand mean + Group 1 vs groups 2, 3, 4 combined + and on we go! + Let's consider the example of the grand mean... --- # Effects coding (sum to zero coding) <!-- --> --- # Sum to zero constraint + With dummy coding we had a reference group constraint, and the mean of that group was equal to the value of `\(\beta_0\)`, or `$$\mu_{reference} = \beta_0$$` + Alternately, we can apply what is referred to as the sum to zero constraint (again using example of three levels). `$$\beta_1 + \beta_2 + \beta_3 = 0$$` + This constraints leads to the following interpretations: + `\(\beta_0\)` is the grand mean (mean of all observations) `$$\beta_0 = \frac{\mu_1 + \mu_2 + \mu_3}{3}$$` + `\(\beta_i\)` are the differences between the coded group and the grand mean: `$$\beta_i = \mu_i - \mu$$` --- # Sum to zero constraint + Finally, we can get back to our group means from the coefficients as follows: `$$\mu_1 = \beta_0 + \beta_1$$` `$$\mu_2 = \beta_0 + \beta_2$$` `$$\mu_3 = \beta_0 - (\beta_1 + \beta_2)$$` --- # OK, but how do we apply the constraint? + Answer, in the same way as we did with dummy coding. + We can create a set of sum to zero (sometimes called effect, or deviation) variables + Or the equivalent contrast matrix. + For effect code variables we: + Create `\(k-1\)` variables + For observations in the focal group, assign 1 + For observations in the last group, assign -1 + For all other groups assign 0 --- # Comparing coding matrices .pull-left[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Level </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> D1 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> D2 </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment A </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment B </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment C </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> `$$y_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta_1D_1 + \beta_2D_2 + \epsilon_{ij}$$` ] .pull-right[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Level </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> E1 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> E2 </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment A </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment B </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment C </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> `$$y_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta_1E_1 + \beta_2E_2 + \epsilon_{ij}$$` ] --- # Sum to zero/effects for group means .pull-left[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Level </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> E1 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> E2 </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment A </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment B </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Treatment C </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> `$$\mu_1 = \beta_0 + \beta_1$$` `$$\mu_2 = \beta_0 + \beta_2$$` `$$\mu_3 = \beta_0 - (\beta_1 + \beta_2)$$` ] .pull-right[ `$$\mu_1 = \beta_0 + 1*\beta_1 + 0*\beta_2 = \beta_0 + \beta_1$$` `$$\mu_2 = \beta_0 + 0*\beta_1 + 1*\beta_2 = \beta_0 + \beta_2$$` `$$\mu_3 = \beta_0 -1*\beta_1 -1*\beta_2 = \beta_0 - \beta_1 -\beta_2$$` + Now we will look practically at the implementation and differences ] --- # Group Means ```r hosp_tbl %>% select(1:2) %>% group_by(Treatment) %>% summarise( mean = round(mean(SWB),3), sd = round(sd(SWB),1), N = n() ) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 4 ## Treatment mean sd N ## <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> ## 1 TreatA 9.33 2.9 60 ## 2 TreatB 11.3 2.5 60 ## 3 TreatC 9.04 2 60 ``` --- # Effects (sum to zero) model + We need to change the contrast scheme from default. ```r contrasts(hosp_tbl$Treatment) <- contr.sum contrasts(hosp_tbl$Treatment) ``` ``` ## [,1] [,2] ## TreatA 1 0 ## TreatB 0 1 ## TreatC -1 -1 ``` --- # Effects (sum to zero) model ```r summary(lm(SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -5.373 -1.987 -0.300 1.838 7.173 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 9.8806 0.1872 52.791 < 2e-16 *** ## Treatment1 -0.5539 0.2647 -2.093 0.0378 * ## Treatment2 1.3928 0.2647 5.262 4.09e-07 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 2.511 on 177 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.1369, Adjusted R-squared: 0.1271 ## F-statistic: 14.04 on 2 and 177 DF, p-value: 2.196e-06 ``` --- # Effects (sum to zero) model .pull-left[ ``` ## (Intercept) Treatment1 Treatment2 ## 9.881 -0.554 1.393 ``` + Coefficients from group means `$$\beta_0 = \frac{\mu_1 + \mu_2 + \mu_3}{3}$$` `$$\beta_1 = \mu_1 - \mu$$` `$$\beta_2 = \mu_2 - \mu$$` ] .pull-right[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Treatment </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> mean </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Gmean </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.327 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatB </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11.273 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatC </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.042 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> --- # Effects (sum to zero) model .pull-left[ ``` ## (Intercept) Treatment1 Treatment2 ## 9.881 -0.554 1.393 ``` + Group means from coefficients: `$$\mu_1 = \beta_0 + \beta_1$$` `$$\mu_2 = \beta_0 + \beta_2$$` `$$\mu_3 = \beta_0 - (\beta_1 + \beta_2)$$` ] .pull-right[ <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Treatment </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> mean </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Gmean </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatA </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.327 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatB </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11.273 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> TreatC </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.042 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.881 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> ] --- # The wide world of contrasts + We have now seen two examples of coding schemes (dummy and effect). + There are **lots** of different coding schemes we can use for categorical variables to make different comparisons. + If you are interested, see the excellent resource on [UCLA website](https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/r/library/r-library-contrast-coding-systems-for-categorical-variables/) + **But always remember...** --- # The data is the same, the tested contrasts differ + Run both models: ```r contrasts(hosp_tbl$Treatment) <- contr.treatment m_dummy <- lm(SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl) # Change the contrasts and run again contrasts(hosp_tbl$Treatment) <- contr.sum m_zero <- lm(SWB ~ Treatment, data = hosp_tbl) ``` + Create a small data set: ```r treat <- tibble(Treatment = c("TreatA", "TreatB", "TreatC")) ``` --- # The data is the same, the tested contrasts differ + Add the predicted values from our models ```r treat %>% mutate( pred_dummy = predict(m_dummy, newdata = .), pred_zero = predict(m_zero, newdata = .) ) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 3 ## Treatment pred_dummy pred_zero ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 TreatA 9.33 9.33 ## 2 TreatB 11.3 11.3 ## 3 TreatC 9.04 9.04 ``` + No matter what coding or contrasts we use, we are still modelling the group means! --- class: center, middle # Time for a break **Deep breaths and a cup of tea** --- class: center, middle # Welcome Back! **But we can still do more...** --- # Manual contrast testing + We can structure a wide variety of contrasts so long as they can be written: 1. A as a linear combination of population means. 2. The associated coefficients (weights) sum to zero. + So $$H_0: c_1\mu_1 + c_1\mu_2 + c_3\mu_3 $$ + With `$$c_1 + c_2 + c_3 = 0$$` --- # Manual contrast testing + For both dummy and effects coding we have seen we assign values for the contrasts + Dummy = 0 and 1 + Effects = 1, 0 and -1 + When we create our own contrasts, we have certain rules to follow in assigning values --- # Rules for assigning weights + **Rule 1**: Weights are -1 ≤ x ≤ 1 + **Rule 2**: The group(s) in one chunk are given negative weights, the group(s) in the other get positive weights + **Rule 3**: The sum of the weights of the comparison must be 0 + **Rule 4**: If a group is not involved in the comparison, weight is 0 + **Rule 5**: For a given comparison, weights assigned to group(s) are equal to 1 divided by the number of groups in that chunk. + **Rule 7**: Restrict yourself to running `\(k\)` – 1 comparisons (where `\(k\)` = number of groups) + **Rule 8**: Each contrast can only compare 2 chunks of variance + **Rule 9**: Once a group singled out, it can’t enter other contrasts --- # New example + Suppose we were interested in the effect of various relationship statuses on an individuals subjective well-being (`swb`) + Keeping with a theme on our outcome. + Our predictor is `status` which has 5 levels: + Married or Cival Partnership + Cohabiting relationship + Single + Widowed + Divorced + Let's say we have data on 500 people. --- # Data <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> status </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> n </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> mean </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> sd </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Cohab </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 100 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11.44 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4.22 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Divorced </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9.37 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2.34 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Married/CP </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 275 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10.63 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3.41 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Single </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8.06 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2.19 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Widowed </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 25 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6.00 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1.07 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> --- # Applying rules + Let's say we want to make two contrasts 1. Those who are currently or previously married or in a civil partnership vs not. 2. Those who are currently married or in a civial partnership vs those who have previously been. <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> group </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> contrast1 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> contrast2 </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Cohab </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Divorced </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.5 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Married/CP </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1.0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Single </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Widowed </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.5 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> --- # `emmeans` + We will use the package `emmeans` to test our contrasts + We will also be using this in the next few weeks to look at analysing experimental designs. + **E**stimated + **M**arginal + **Means** + Essentially this package provides us with a lot of tools to help us model contrasts and linear functions. --- # Orthogonal vs. Non-orthogonal Contrasts + Orthogonal contrasts test independent sources of variation. + If we follow the rules above, we will have orthogonal contrasts. + Non-orthogonal contrasts test non-independent sources of variation. + This presents some further statistical challenges in terms of making inferences. + We will come back to this discussion later in the course. --- # Rule 10: Checking if contrasts are orthogonal + The sum of the products of the weights will = 0 for any pair of orthogonal comparisons `$$\sum{c_{1j}c_{2j}} = 0$$` --- # From our example ```r contrasts %>% mutate( Orthogonal = contrast1*contrast2 ) %>% kable(.) %>% kable_styling(., full_width = F) ``` <table class="table" style="width: auto !important; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> group </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> contrast1 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> contrast2 </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Orthogonal </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Cohab </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.000 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Divorced </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.165 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Married/CP </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1.0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.330 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Single </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.50 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.000 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Widowed </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0.33 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> -0.165 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> --- # Summary of today + We have considered different ways in which we can code categorical predictors. + Take home: + Use of coding matrices allows us to compare groups (or levels) in lots of ways. + Our `\(\beta\)`'s will represent differences in group means. + The scheme we use determines which group or combination of groups we are comparing. + **In all cases the underlying data is unchanged.** + This makes coding schemes a very flexible tool for testing hypotheses. --- class: center, middle # Thanks for listening!