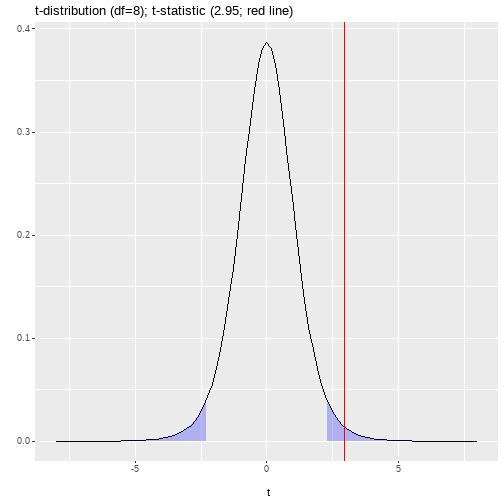

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # <b>Model coefficients</b> ## Data Analysis for Psychology in R 2<br><br> ### dapR2 Team ### Department of Psychology<br>The University of Edinburgh --- # Week's Learning Objectives 1. Be able to specify a simple linear model. 2. Understand and describe fitted values and residuals. 3. Be able to interpret the coefficients from a linear model. 4. Be able to test hypotheses and construct confidence intervals for the model coefficients. --- # Topics for today + Now we know how to position our model line, we can consider: + Interpreting the values + Testing the significance --- # Things to recap + We will look again at significance testing. + And also discuss sampling variability. + If at any point you feel like you are not following this section of the material, go back and review sampling and hypothesis testing material linked on LEARN. --- # Recap linear model + The linear model for a single predictor is written as: `$$y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i} + \epsilon_i$$` + `\(\beta_0\)` = **Intercept**: the point where the line cross `\(y\)`, and `\(x\)` = 0 + `\(\beta_1\)` = **Slope**: the gradient of the line, or rate of change + In our worked example we saw how to calculate the intercept and slope from the raw data. --- # `lm` in R + We do not generally calculate by hand like this, so we also briefly introduced the `lm()` function. ```r lm(score ~ hours, data = test) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = score ~ hours, data = test) ## ## Coefficients: ## (Intercept) hours ## 0.400 1.055 ``` --- # Interpretation + **Slope is the number of units by which Y increases, on average, for a unit increase in X.** -- + Unit of Y = 1 point on the test + Unit of X = 1 hour of study -- + So, for every hour of study, test score increases on average by 1.055 points. -- + **Intercept is the expected value of Y when X is 0.** -- + X = 0 is a student who does not study. -- + So, a student who does no study would be expected to score 0.40 on the test. ??? + So we know in a general sense what the intercept and slope are, but what do they mean with respect to our data and question? --- # Note of caution on intercepts + In our example, 0 has a meaning. + It is a student who has studied for 0 hours. + But it is not always the case that 0 is meaningful. + Suppose our predictor variable was not hours of study, but age. + **Look back at the interpretation of the intercept, and instead of hours of study, insert age. Read this aloud a couple of times.** -- + This is the first instance of a very general lesson about interpreting statistical tests. + The interpretation is always in the context of the constructs and how we have measured them. --- class: center, middle # Time for a break **Quiz time!** --- class: center, middle # Welcome Back! **Where we left off... ** We have gone over interpreting our coefficients. Now we can start to look at how we evaluate our model --- # Evaluating our model + At this point, we have estimated values for the key parameters of our model (intercept and slope). + Now we have to think about how we evaluate the model. + There are three ways to think about evaluation: 1. Evaluating the individual coefficients 2. Evaluating the overall model quality 3. Evaluating the model assumptions + Before accepting a set of results, it is important to consider all three of these aspects of evaluation. ??? Important to really emphasize this is a package of information and we want it all before we decide to accept our model. --- # Significance of individual effects + A general way to ask this question would be to state: > **Is our model model informative about the relationship between X and Y?** -- + In the context of our example from last lecture, we could ask, > **Is study time a useful predictor of test score?** -- + The above is a research question/hypothesis. As we have done before, we need to turn this into a testable statistical hypothesis. --- # Evaluating individual predictors + Steps in hypothesis testing: -- + Research questions -- + Statistical hypothesis -- + Define the null -- + Calculate an estimate of effect of interest. -- + Calculate an appropriate test statistic. -- + Evaluate the test statistic against the null. --- # Research question and hypotheses + **Research questions** are statements of what we intend to study. + A good question defines: -- + Constructs under study + the relationship being tested + A direction of relationship + target populations etc. > **Does increased study time improve test scores in school age children?** -- + **Statistical hypotheses** are testable mathematical statements. -- + In typical testing in Psychology, we define have a **null ( `\(H_0\)` )** and an **alternative ( `\(H_1\)` )** hypothesis. + `\(H_0\)` is precise, and states a specific value for the effect of interest. + `\(H_1\)` is not specific, and simply says "something else other than the null is more likely" ??? Flag here that if these comments are completely alien to them, they should go back and recap the hypothesis testing material from dapR1-lectures 12 to 15 (20-21) or 12-14 (19-20). --- # Defining null + Conceptually: + If `\(x\)` yields no information on `\(y\)`, then `\(\beta_1 = 0\)` + **Why would this be the case?** -- + `\(\beta\)` gives the predicted change in `\(y\)` for a unit change in `\(x\)`. + If `\(x\)` and `\(y\)` are unrelated, then a change in `\(x\)` will not result in any change to the predicted value of `\(y\)` + So for a unit change in `\(x\)`, there is no (=0) change in `\(y\)`. + We can state this formally as a null and alternative: `$$H_0: \beta_1 = 0$$` `$$H_1: \beta_1 \neq 0$$` ??? + For the null to be testable, we need to formally define it. + Point out here the difference in the specificity of the hypotheses. `\(H_0\)` is that the `\(b_1\)` takes a specific value. `\(H_1\)` is that `\(b_1\)` has some value that is not this specific value. i..e one is directly testable, the other is not. --- class: center, middle # Time for a break **Quiz time** We are about to look at hypothesis tests for coefficients. So our quiz is on the concept of the standard error --- class: center, middle # Welcome Back! **Where we left off... ** We have defined a null, now let's look at constructing the test --- # Point estimate and test statistic + We have already seen how we calculate `\(\hat \beta_1\)`. + The associated test statistic to for `\(\beta\)` coefficients is a `\(t\)`-statistic `$$t = \frac{\hat \beta}{SE(\hat \beta)}$$` + where + `\(\hat \beta\)` = any beta coefficient we have calculated + `\(SE(\hat \beta)\)` = standard error of `\(\beta\)` -- + **Recall** that the standard error describes the spread of the sampling distribution. + The standard error (SE) provides a measure of sampling variability + Smaller SE's suggest more precise estimate (=good) ??? + brief reminders on test statistics + every quantity we wish to calculate a significance test for needs an test statistic. + the test statistic is a value that has a known sampling distribution + If sampling distribution is unfamiliar, again, recap the hypothesis testing material --- # SE( `\(\hat \beta_1\)` ) + The formula for the standard error of the slope is: `$$SE(\hat \beta_1) = \sqrt{\frac{ SS_{Residual}/(n-k-1)}{\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2}}$$` + Where: + `\(SS_{Residual}\)` is the residual sum of squares + `\(n\)` is the sample size + `\(k\)` is the number of predictors (= 1 for simple linear regression) + **Given the above, think about what things would make the SE smaller.** -- + From this formula, we can see that the SE's for `\(\beta\)` will be smaller when: + Residual variance ( `\(SS_{Residual}\)` ) is smaller + Sample size, `\(n\)`, is larger --- # Back to the example `$$t = \frac{\hat \beta_1}{SE(\hat \beta_1)}$$` + Let's calculate `\(t\)` for our example. + We will use some values we have already calculated + `\(\hat \beta_1 = 1.055\)` -- + So we need `\(SE(\hat \beta_1)\)` `$$SE(\hat \beta_1) = \sqrt{\frac{SS_{Residual}/(n-k-1)}{\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2}}$$` + `\(n\)` = 10 + `\(k\)` = 1 + `\(\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2\)` = 20.625 --- # Back to the example + So all we have left is `\(SS_{Residual}\)`. + From earlier this week, we know: `$$SS_{Residual} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2$$` + `\(SS_{Residual}\)` = residual sum of squares = sum of the squared residuals ```r res <- lm(score ~ hours, data = test) SSRes = sum(res$residuals^2) SSRes ``` ``` ## [1] 21.16364 ``` --- # Back to our example + So pull all this together: `$$SE(\hat \beta_1) = \sqrt{\frac{SS_{Residual}/(n-k-1)}{\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2}} = \sqrt{\frac{21.16364 / (10-1-1)}{20.625}} = \sqrt{\frac{2.65455}{20.625}} = 0.35814$$` -- + and finally `$$t = \frac{\hat \beta_1}{SE(\hat \beta_1)} = \frac{1.055}{0.35814} = 2.945773 = 2.95$$` --- # Sampling distribution for the null + Now we have our `\(t\)`-statistic, we need to evaluate it. + For that, we need sampling distribution for the null. + For `\(\beta\)`, this is a `\(t\)`-distribution with `\(n-k-1\)` degrees of freedom. + Where `\(k\)` is the number of predictors, and the additional -1 represents the intercept. -- + So for linear models with 1 predictor this is `\(n-2\)` + In our case = 8 --- # A decision about the null + So we have a `\(t\)`-value associated with our `\(\beta\)` coefficient. + t = 2.95 + And we know we will evaluate it against a `\(t\)`-distribution with 8 df. + As with all tests we need to set our `\(\alpha\)`. + Let's take 0.05 two tailed. -- + Now we need a critical value to compare our observed `\(t\)`-value to. --- # Visualize the null .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ + Critical value and `\(p\)`-value: ```r tibble( LowerCrit = round(qt(0.025, 8), 3), UpperCrit = round(qt(0.975, 8), 3), Exactp = (1 - pt(2.95, 8)) * 2 ) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 1 x 3 ## LowerCrit UpperCrit Exactp ## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 -2.31 2.31 0.0184 ``` ] ??? + discuss this plot. + remind them of 2-tailed + areas + % underneath each end + comment on how it would be different one tailed + remind about what X is, thus where the line is --- # `lm` in R .pull-left[ ```r summary(res) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = score ~ hours, data = test) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -1.6182 -1.0773 -0.7454 1.1773 2.4364 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 0.4000 1.1111 0.360 0.7282 ## hours 1.0545 0.3581 2.945 0.0186 * ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.626 on 8 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.5201, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4601 ## F-statistic: 8.67 on 1 and 8 DF, p-value: 0.01858 ``` ] .pull-right[ + So in our example, we **reject the null**. + **Spend a little bit of time looking at this output, and comparing the various values to those things we calculated in our example.** + Some we haven't yet looked at. + They are coming next. ] --- # Confidence intervals for `\(\beta_1\)` + We can also compute confidence intervals for `\(\hat \beta_1\)` + The `\(100 (1 - \alpha)\)`, e.g., 95%, confidence interval for the slope is: `$$\hat \beta_1 \pm t^* \times SE(\hat \beta_1)$$` + So, 95% confidence interval for in our revision and test score example would be: ```r tibble( LowerCI = round(1.055 - (2.306 * 0.358), 3), UpperCI = round(1.055 + (2.306 * 0.358), 3) ) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 1 x 2 ## LowerCI UpperCI ## <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 0.229 1.88 ``` + The confidence interval of 0.229 to 1.881 does not include zero, + Therefore, we can conclude that **revision is a statistically significant predictor of test scores** ( `\(p < .05\)`). --- # Summary of today + Interpretation of `\(\beta_0\)` and `\(\beta_1\)` + Conducting a hypothesis test for `\(\beta_1\)` + Calculating confidence intervals for `\(\beta_1\)` --- class: center, middle # Thanks for listening!