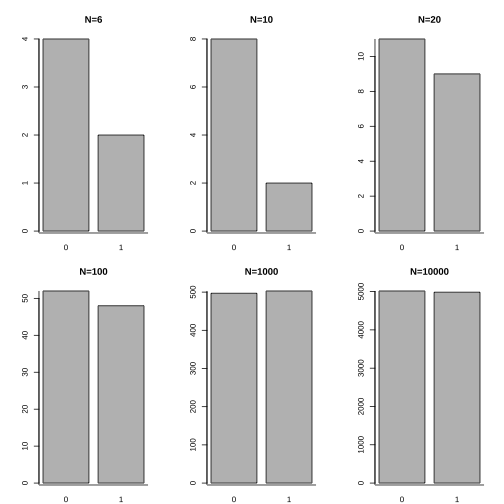

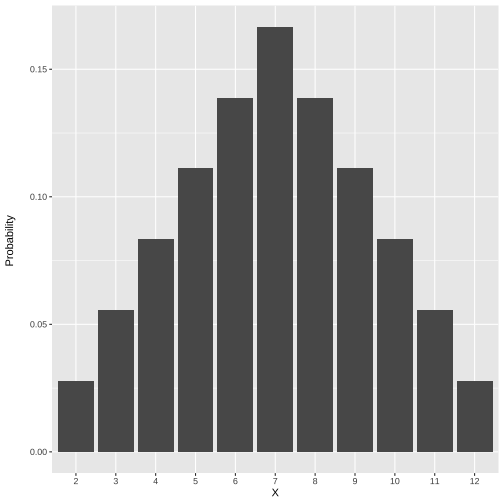

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # <b>Lecture 6: Introduction to Probability </b> ## Data Analysis for Psychology in R 1<br><br> ### ALEX DOUMAS & TOM BOOTH ### Department of Psychology<br>The University of Edinburgh ### AY 2020-2021 --- ## Today - Why do we need probability? - Some concepts about sets - Assigning probability - basic rules --- ## Learning objectives - Understand the link between probability, models and data - Understand the basic rules of probability - (From lab) being able to apply these rules --- ## Why probability? + Consider the statements: -- + There is a 50\50 chance of a fair coin landing on Heads -- + There is a `\(\frac{13}{52}\)` chance of drawing a heart in a deck of cards -- + In both cases, we are presenting something based on known information about the world. + *We have a model for the world*. -- + But we do not have data. + We do not have, for example, any results from tossing an actual coin. --- ## Why probability? - In statistics and data analysis, often the opposite is true. -- - We have some data, but we do not know the *truth of the world* - We have to make inferences about it. -- - In order to make these inferences, we are going to use probability, and models of the world based on it. -- - But before we do, we need to build up some concepts. --- ## What is probability? + There are two ways to conceptualise probability (they both end up in the same place, and you can use whichever one makes more sense to you. -- 1. Analytic definition: + If there are `\(a\)` ways in which `\(x\)` can occur and `\(b\)` ways in which `\(x\)` can fail to occur, then `\(P(x) = a/(a+b)\)` + If a bag contains 85 light and 15 dark caramels and you reach into the bag randomly and grab a caramel, P(light) = 85/(85+15) = .85 (or 85%) --- ## What is probability? + There are two ways to conceptualise probability (they both end up in the same place, and you can use whichever one makes more sense to you. 1. Analytic definition 2. Relative frequency: + `\(P(x)\)`, or probability of x, is the proportion of times you would observe `\(x\)` if you took an infinite number of samples. + If I roll a die an infinite number of times, the probability I would roll a 1 would be exactly 1/6. --- ## What is probability? - The long run, or the *law of large numbers* - Given an event `\(A\)` and a probability `\(P(A)\)`, over N trials, the probability that the relative frequency of `\(A’\)` will differ from `\(P(A)\)` approaches 0 as N approaches infinity --- ## What is probability? - What does all that stuff get us? -- - Basic idea: probability of *x* is: ways *x* can happen divided by all the ways that all things (including *x*) can happen. -- - So, in its most essential sense, the business of probability is figuring out what those two numbers (ways *x* can happen ; ways that all things can happen). -- - Generally, we base these calculations on structures called *sets*... --- ## Sets - Probabilty is built on the theory of sets. -- - **Set**: Well-defined collection of objects. -- - Sets are composed of **elements** or **members** - E.g. students in class - E.g. real numbers between 0 and 1 --- ## Set notation - `\(d \in D\)` - d is an element of D - `\(e \notin D\)` - e is not an element of D - F = {f `\(\mid\)` f in an integer, `\(1 \leq f \leq 10\)`} - F includes elements **such that** f is an integer greater tan or equal to 1 and less than or equal to 10. --- ## Sets - **Universal Set**: A set of all elements we are concerned with. - **Subset**: A Set B is a subset of A if and only if every `\(x \in B\)`, then `\(x \in A\)` - `\(B \subseteq A\)`, B is a subset of A - **Proper subset**: a Set B is a proper subset of A if B is a subset of A and at least one member of A is NOT a member of B - `\(B \subset A\)`, B is a proper subset of A --- ## Sets: and or <img src="./figures/union_int.PNG" width="60%" /> --- ## Sets: Empty, complement, difference <img src="./figures/empty.png" width="60%" /> - Key point on empty sets: P and R here are **mutually exclusive** - If P occurs, R **cannot** occur. --- ## Does some of it seem familiar? - Working with sets is often referred to as Boolean algebra - You have some across this when you work with logicals in R. --- ## Sets & Probability - In probability we talk about a *sample space* -- - Sample space (S) = all possible outcomes (or the ways that things can happen). -- - Every point in this sample space is a single outcome. -- - An event (A)is a set of outcomes from S -- - A *simple event* (a) = single point such that `\(a \in S\)` -- - *Random experiment* = sampling of simple events from a sample space. --- ## A random experiment - Let's consider a simple random experiment. - Imagine tossing a coin a bunch of times... --- ## Coin toss <!-- --> --- ## Aside... - Test your comhrehension. - Go back to the last slide with the results of the coin toss experiments and pause the recording. - What concept does the figure illustrate? - Pause... -- - Answer: The law of large numbers. --- ## Example - Suppose we have the following experiment. - We roll two six-sided dice. - The outcome is the sum of the numbers on the upward pointing space. --- ## Example: Sample Space | | **1** | **2** | **3** | **4** | **5** | **6** | |---|---|---|---|----|----|----| | **1** | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | | **2** | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | | **3** | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | | **4** | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | | **5** | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | | **6** | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | --- ## Example: Probabilities | **Simple Event** | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |------------------|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|----|----|----| | **Frequency** | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | | **Probability** | `\(\frac{1}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{2}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{3}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{4}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{5}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{6}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{5}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{4}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{3}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{2}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{36}\)` | --- ## Example: Probability Distribution <!-- --> ??? - A probability distribution maps the values of a random variable to the probability of it occurring. --- ## Probability from sets - `\(P(i)\)` = probability of event `\(i\)` -- - `\(0 \leq P(i) \leq 1\)` = probability of event `\(i\)` is between 0 and 1 -- - `\(P(i_1) + P(i_2) + ... + P(i_n) = P(S)\)` = probability of all events in sample space `\(S\)` = 1 -- - `\(P(i) + P(\sim i) = 1\)`, so `\(P( \sim i) = 1 - P(i)\)` ??? Note from sets we know: 1. Probability can't be less than 1 because there are at minimum 0 ways x can occur; and probability can't be more than 1 because there cannot be more ways x can occur than possible outcomes. 2. All of the possible outcomes make up all the ways that things can occur. Therefore, if you add up all the outcomes you get ways (i.e., way1+way2+way3+... == ways), and ways/ways == 1. 3. If the probability of x is x/ways, and notx is notx/ways, and x and not-x make up all the possible ways, then by definition x+notx == ways so x+notx/ways == 1 --- ## Joint Probability - Probability of A **and** B = `\(p(A \bigcap B)\)` - Joint event or *intersection* of A and B -- - Probability of A **or** B = `\(p(A \bigcup B)\)` - *Union* of A and B -- - Probability of **not** A = `\(p(\sim A)\)` - We describe the event not A as the *complement* of A. --- ## Relations between events - **Mutually exclusive** events: If A occurs, B can not occur. - **Independent** events: The occurance of event A does not impact event B. - **Dependent** events: The occurance of event A **does** impact event B. - Impact means that A changes in the probability of B. --- ## Probabilities of joint events - For mutually exclusive events, the probability of the union of those events is the sum of the individual probabilities. -- - Think of the coin example: `$$p(Head \bigcup Tails) = p(Head) + p(Tails) = 0.5 + 0.5 = 1.0$$` --- ## Probabilities of joint events - For non-mutually exclusive events. `$$p(A \bigcup B) = p(A) + p(B) - p(A \bigcap B)$$` -- - Why? `$$p(king or heart) = \frac{4}{52} + \frac{13}{52} - \frac{1}{52} = \frac{4}{13} = 0.31$$` --- ## Probabilities of joint events - So far we have looked at rules for unions (or), but what about intersections (and) events: -- - If events are independent, then; `$$p(A \bigcap B) = p(A)p(B)$$` -- - Consider getting a success (Head) in a coin flip (event A), and cutting the deck on a heart (event B). `$$p(A \bigcap B) = \frac{1}{2} * \frac{1}{4} = \frac{1}{8} = .125 = 12.5%$$` -- - What if events are not independent? -- - We'll cover that next lecture. - For now let's have a quick but important aside... --- ## Sampling: With and without replacement - In the lab there were examples of the use of `sample()` with `replace=T` and `replace=F` -- - What does that mean? - Imagine a bag of balls, 6 red 4 blue. - We take 1 ball - `\(p(red) = \frac{6}{10} = \frac{3}{5}\)` = 0.60 - `\(p(blue) = \frac{4}{10} = \frac{2}{5}\)` = 0.40 --- ## Sampling: With and without replacement - If we put the ball back, then the probabilities are the same next draw. - If we keep the ball, then the probabilities change... -- - If we assume it was red, then; - `\(p(red) = \frac{5}{9}\)` = 0.56 - `\(p(blue) = \frac{4}{9}\)` = 0.44 --- ## Sampling: With and without replacement - Whether we replace or not matters with respect to thinking about multiple trials. - If we draw two balls from the sample, what is the probability they are both red? - As long as the events are independent, then: - **With replacement** = 0.6*0.6 = 0.36 = 36% - **Without replacement** = 0.60*0.56 = 0.34 = 34% --- # Summary of today 1. `\(P(x)\)` is `\(x/y\)` where *x* is ways *x* can happen and *y* is ways all things (including *x*) can happen. 2. Sets help us conceptualise *x* and *y*. 3. Rules for sets help us define rules for probability. --- # Next tasks + Next week, we will continue to look at probability + This week: + Complete your lab + Come to office hours + Come to Q&A session + Weekly quiz - on week 5 content + Open Monday 09:00 + Closes Sunday 17:00